A human professional musician is of course faster than our sounds. We have 1.5 million samples, but real musicians have more. I don’t think we’ll ever get them all. I don’t think orchestras are threatened. In the TV industry, for example, they don’t have the budgets for orchestras anyway. And there are still live performances. Nobody goes to a concert to listen to a computer.”

— Herb Tucmandl, Vienna Symphonic Library, 2006.

DSM: Working for Vienna Symphonic Library would have to be the ultimate conflict of interest for a musician—helping to build a digital sound library that can reduce the need to have a full complement of live musicians. Live performing gigs are plentiful in Europe, but aren’t so abundant in North America.

CMT: Classical musicians have long opposed replacing live artists with computers in concert performances. This has gotta be one of the most compelling reasons why. The VSL sounds are that good! I never thought I would say so but, yes, the digitally sampled waveform libraries, like VSL, and all of the articulation and technic options are finally that good!

DSM: Today’s Wall Street Journal has an article describing the plan of conductor Paul Henry Smith to produce three Beethoven symphonies back-to-back in a concert with an "orchestra" having no live musicians—just sequenced waveforms from the Vienna Symphonic Library.

CMT: The conventional stance has musicians opposing the substitution of digital virtual instruments and sequencers for live musicians in orchestras, ballets and opera houses.

DSM: But yet some composers, conductors, musicians and engineers actually feel that embracing the use of virtual instruments holds promise for keeping classical music alive.

CMT: And of course touring musicals and acts like Cirque du Soleil have used virtual instruments for a number of years. Those incursions are harmful enough, but the impact is modest—simply because the number of shows and engagements per year is relatively small. And the musicians’ unions’ efforts do keep virtual orchestras out of Broadway orchestra pits so far. But in London a virtual orchestra has been used in Cameron Mackintosh’s revival of ‘Les Misérables.’ We seem now to finally be on the slippery slope. It’s not hypothetical anymore. The worry has a basis in reality. Even a paranoid has real enemies!

DSM: It’s true that composers of new music who couldn't otherwise afford to have their compositions performed by a live orchestra can now commission a high-quality software-generated recording for a few thousand dollars.

CMT: But what about communities that stand to lose their orchestra due to negative cashflow? A digital waveform library and sequencer-based virtual orchestra stands in for half the players? It’s a drink, but it’s not the martini I wanted!

DSM: I’ve got a copy of GIGA Virtual Instrument and a copy of VSL. I use both with Finale, as a way to hear what I’ve written and revise it or change my voice-leading to make sure I’ve got the texture right. The quality of the libraries is definitely good enough for that purpose. And good enough to record a demo, so that I can get string quartets interested in playing what I’ve written. But—I agree—playing a sequencer in front of a paying audience seems like a travesty. It’s not the martini they wanted.

CMT: There’s a big difference between theatre where the musicians are hidden and theatergoers are mainly buying an experience with live actors, and concerts where concertgoers are mainly buying an experience with live musicians. Would theatergoers be satisfied with holographic, sequenced digital imagery of a play onstage? I doubt it! There’s no intimacy in it. There’s no risk or uncertainty. So why should a concertgoer be any different, with regard to virtual instruments? Where is the intimacy? Where’s the authenticity? Where’s the real-time interaction with an audience?

DSM: Herb Tucmandl, founder of the Vienna Symphonic Library, acknowledges that virtual instruments do change the competitive landscape. Nothing is value-neutral. In an era obsessed with driving out cost and optimizing efficiency the virtual instruments aid and abet the buyer and undermine the musician-seller. But classical musicians should take control and become fluent in this technology instead of complaining about it or ignoring it. It’s not possible to turn back the clock. In that way, the new virtual instrument trend is just an extension of the MIDI and synthesizer boom that began in the 1980s. Many keyboardists adapted to that and became proficient in using synths. But many older ones did not. So the ‘digital divide’ is not just about internet access or web-enabled social networking. It’s the more general process of technology disenfranchising human beings and eroding the number and the value of the opportunities still available to human beings.

CMT: You have to admit, though, that the virtual instruments are pretty good these days as far as the sound qualities are concerned—the attacks and decays and timbre and other parameters. Virtual instruments should provide satisfying control over sound—comparable to the control that an expert musician has over a fine acoustic instrument. These elements are necessary for virtual instruments: low latency of only a few milliseconds; virtually no jitter; realistic representation of all of the technic and artifacts of actual performance on the instrument in each of its registers; precise and accurate sensing; reproducibility; and reliability. Current-generation virtual instruments and sequencers have got all that. But what about silence? It’s not yet possible for virtual instruments and sequencers to deliver fully realistic and many-timbred silences as powerful as we normally get in live performances. This is the kind of musicmaking one expects in concert.

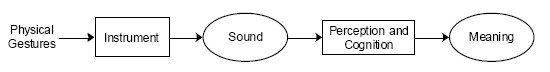

DSM: It’s difficult to produce a variable delay for an audio signal without pitch shifting or complex granular techniques, if you think in terms of an event representation such as MIDI output by a keyboard. Synthesized sounds with sharp attacks illustrate what I mean. The question is: how large of a range of latency can the sequencer-driven system impose without adversely affecting the rhythm that the remaining human performers play? Builders of sensor-based instruments should experiment for themselves with the tolerability of different amounts of jitter. The musically acceptable amount of jitter depends on the kinds of sounds you’re producing. At one extreme are examples such as dense textures and timbral changes in sustaining sounds, where latency and jitter up to even 200ms may have very little impact in the musical result. In the middle is the common case of each gesture causing an individual note to be played. For a skilled performer, jitter of around 10 ms makes the difference between feeling that she does or does not have complete control of rhythms played on the instrument. The other extreme is illustrated by strings of notes played in very rapid succession on the same instrument. Unevenness of just one millisecond of jitter in that situation is audible.

CMT: In this age of email and instant messaging and video games, it’s a treat to savor the wit and eloquence of live artists in an intimate and revealing dialogue. That’s the main beauty and appeal of chamber music. And while the issue discussed in the WSJ article seems mainly one that concerns symphonic or large orchestral productions right now, you can’t help but feel that slippery slope underfoot. What’s next? In the future, will we be confronted with smaller chamber ensembles, with some members substituted with virtual instruments controlled by sequencer applications?

DSM: Did the unions have objections to Music Concrète and electroacoustic music? Years ago, were there lawsuits about the incorporation of tape-loop or other machine sound effects?

CMT: I don’t believe the issue was a prominent one in past decades, mainly because the nature of those effects was outside the realm of traditional performance—a human musician could not make those sounds on a conventional instrument. The other aspect was that the performance required a human operator to man the console—and as long as that person was union, then it was regarded as just another ‘instrument’ among many. Not like it is now, with virtual instruments and a sequencer able to replace an entire orchestra.

DSM: While there are beneficial uses for the virtual instruments (like some we’ve mentioned above), it’s hard to think of their intrusion into concerts or other live performance contexts as anything other than a commodifying influence, depressing wages for musicians and reducing the overall number of gigs per year. The AFM and MU positions on this trend are therefore readily understandable. Think about it. If lawyering is a performance art, then would lawyers sit still for software and artificial intelligence application software preparing virtual briefs and arguing before the court, eliminating many human lawyer engagements per year? I doubt it!

CMT: Right. Their years of preparation as lawyers are aimed at delivering live human legal acumen and insight. Our years of preparation as musicians are aimed at knowing and loving the music so well that we inhabit it as we play. To offer it in performance to an audience opens the possibility of their being drawn into its orbit and understanding it and loving it. A virtual instrument forecloses on that interpersonal offering, to about the same degree—no more, no less—that a recording does.

DSM: For string players, it’s astonishing that any novice has the perseverance to persist past the out-of-tune, scratchy-tone stage. No frets to mark the notes, so the left-hand fingers must learn their spacing to the accuracy of a millimeter in order to create decent pitches. It usually takes many years before reliable accuracy is developed, and it requires constant vigilance to retain it. Precise spatial memory must be coupled with strength, suppleness, speed and stamina—the athleticism of that is partly what the audience sees in live performance. Meanwhile the right arm and hand must learn the movements required, too, a butter-smooth fluidity to set the strings vibrating evenly. The bow not only coaxes the sound from the instrument, but also conjures the colors and emotions in the sound and traces the contours of the phrases—you give voice to the music itself. The right hand must know the action of the bow on the strings, constantly adjusting its speed and weight. And of course, both hands must be perfectly coordinated. Where is that in a performance involving virtual instruments of sampled waveforms of anonymous performers in a studio?

CMT: Even when your technic is under control, each piece of music demands technical and expressive understanding, the hands learning to negotiate the notes and then committing them to kinesthetic memory. With virtual instruments, all of that’s bypassed. The audience knows it. That’s part of why I think a virtual performance lacks authenticity.

DSM: Your kinesthetic memory point is true enough, but there’s an obverse side as well. To be emotionally open as a live performer means avoiding reflexive playing. The reflexes are there: they’re what your kinesthetic conditioning establishes. But the muscle-memory is what frees you in performance to switch your autopilot off. We’re living at a time when intensity in performance is considered obligatory. But great art doesn’t shout all the time. It knows that there is enormous power in gentleness and understatement. Some pieces even require a dry, cold detachment to accurately convey their meaning. The problem with many of the excellent virtual instrument libraries available these days is that the sounds are too wet, too intense. They shout ‘virtuoso’! It’s doubtful that the myriad options available to you when you lay down your GVI tracks adequately cover the dry-and-detached end of the spectrum.

CMT: And music isn’t always earnest and serious. A mature work of art often reflects an integrated view of life and contains humor and wit and irony. I can’t readily find humorous or witty bowings in the Vienna Symphonic Library.

DSM: No matter how many times the music is played, we need to be able to capture the spontaneity of the moment. The virtual performance will never come alive the way that a live performance will, no matter how much you improve the digital “jacket” sensors and artificial-intelligence algorithms for modulating the dynamics and articulations based on the remaining humans’ motions.

CMT: Our duty as musicians is to breathe life into the music, to re-create it with all the excitement and commitment of the composer, or to reinterpret it in valid ways that the composer may not have thought of. It’s an act that renders us both humble and powerful. The paradox is that it is only by being intensely alive as ourselves that we can be entirely at the service of the music and the audience.

DSM: I agree. And your point illustrates another aspect of what seems to me inauthentic about virtual instruments: the absence of community. A sequencing of virtual instruments is typically arranged by a single musician, and the track(s) that result reflect the aesthetic and technical judgments of just that one person. By contrast, the beauty of chamber ensembles derives from the real-time conversational interactions and freedom of several distinct personalities and intellects. With virtual instruments, what we get is one person’s account of the meanings that the music contains. We miss the tension and disputes and surprises.

CMT: Ultimately, with virtual instruments, it’s hard for me to see how either the performer or the listener could be lifted into an enchanted space where diverse shades of emotion are brought into play. ‘Authenticity’ to me means reconnecting to our innermost being. That’s the drink that I ordered! Virtual instruments are a boon for composers, but not for many others.

- Informatica Musicale, Univ Padova, Italy [CreativeCommons pdf files]

- Russell J, Jurgensen J. Fugue for Man & Machine. Wall Street Journal, P1, 05-MAY-2007.

- Vienna Symphonic Library

- IRCAM Virtual Orchestra website

- American Federation of Musicians (AFM) union website

- Lennon D. [Virtual Orchestra] Perpetrator Turns Into ‘Victim.’ AFM Local 802 newsletter. Allegro 2004 April;104(4) [HTML article]

- Musicians' Union, U.K.

- Picard R. Affective Computing. MIT, 2000.

T o obtain an exception to the minimum musician requirement, a League member must demonstrate that there are legitimate artistic reasons why the production should be permitted to use fewer than the required number of musicians. An application for an exception is first reviewed by a Special Situations Committee (“Committee”), comprised of experts in the field of theatrical production, who are chosen in advance by the Parties. (Pet. ¶ 10, Ex. A at 11.) FN3 Both Parties may present documentary evidence and call witnesses when they appear before the Committee. (Pet.¶ 10.) The Committee is required under the Agreement to “decide the issue primarily on artistic considerations.” (Pet. Ex. A at 12.) Specifically, the Committee is to consider four factors:After considering the Parties’ presentations, the Committee must render a written decision explaining in detail the basis for its conclusions within forty-eight hours after the Parties have submitted their positions. (Pet. ¶ 10, Ex. A at 12.).”

- the musical concepts expressed by the composer and/or orchestrator;

- whether the production is of a definable musical genre different from a traditional Broadway musical;

- the production concept expressed by the director and/or choreographer; and/or

- whether the production recreates a pre-existing size band or band’s sound (on or offstage). (Pet. Ex. A at 12.)

— United States District Court, S.D. New York, ASSOCIATED MUSICIANS OF GREATER NEW YORK, LOCAL 802, AFM, Petitioner v. The LEAGUE OF AMERICAN THEATRES AND PRODUCERS, INC., Respondent. Slip Copy, 2006 WL 3039995, No. 05-CV-2769 (KMK), Oct. 25, 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment