A cadenza is meant to be improvised and should be performed as though it had just occurred to the performer. But, as it is risky for most players to improvise it on the spot, they ought to write it down or at least sketch it in advance... It is as little possible to prescribe good cadenzas… as it is to teach someone to memorize flashes of ‘wit’ beforehand.”

— Daniel Gottlob Türk, Klavierschule, 1789.

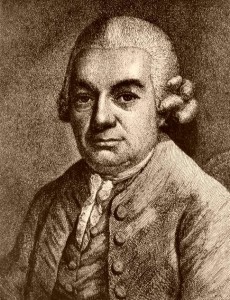

I It is well known that Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was connected to a wide circle of philosophers, theologians, poets and music critics—both in Berlin, where he worked as court harpsichordist to Frederick the Great, and in Hamburg, where he took up the post as director of music of the city’s churches from 1768. One of the central debates within these intellectual circles concerned the nature of artistic expression and its relationship to the self.”T here have been lots of ‘hits’ on the CMT post that I put up a couple of days ago, on Mozart’s ‘Wurfelspiel’ minuet generator—oddly many. Also, a number of emails from readers asking whether I meant the post to be—or, alternately, whether Mozart meant K.516f to be—an attack on minuet form as ‘banal’. Hmmm!

— Rachel Baldock, Understanding [C.P.E.] Bach, 2008.

W ell, no! Neither is true! Nor were early aleatoric compositional methods intended as pranks or idle curiosities, probably. I bet the instances that we know of—Mozart’s, Haydn’s, C.P.E. Bach’s, others’—were bona fide musical experiments, meant to earnestly see where things could go… intended to ‘push the envelope’ of compositional techniques and musical experience.

I n 1753 C.P.E. Bach wrote his ‘Versuch’ treatise, and he devoted the long last chapter entirely to how to improvise fantasias. He strongly recommended ‘free improvisation’ and thought that one effective way to encourage it was by [Sacrebleu!] eliminating the bar lines in the score.

B asically, he used randomization to generate sudden emotional contrasts. In the spirit of the so-called ‘Empfindsamer Stil’ for which C.P.E. Bach was famous, the performer/listener was meant to ‘go with the flow’, suspend disbelief, and ‘submit’ to the rite... Allow the evolving and contrasting moods of the composition to carry himself/herself away.

T his was not a superficial pandering to prevailing ‘market’ mores; it was C.P.E. Bach’s experiment in navigating the emotions—and an experiment in discovering what musical gestures were (or were not) effective in rapidly eliciting genuine feelings. Pamela Fox wrote a famous article about C.P.E. Bach’s ‘stylistic non-constancy’ about 20 years ago. But she didn’t speculate much about C.P.E. Bach’s motivations or psychological intentions. Pamela did not write about trances or ecstatic, mystical states…

T The public demands that practically every idea be constantly altered, sometimes without investigation whether the structure of the piece or the skill of the performer permits such alteration... One no longer has the patience to play the written notes [even] for the first time.”F or me, the process I experience is as though C.P.E. Bach were aiming at ‘startling’ us players or listeners with sudden changes in dynamics, with altered rhythmic patterns, with unexpected modulations.

— C.P.E. Bach, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard.

T ake the ‘Concerto in F Major for Two Harpsichords’, Wq. 46 [H. 408], for example. There are some aleatoric elements in here, but these are only half-explicit... scored, but not entirely prescribed by C.P.E. And they are not the ‘frozen improvisations’ of the illustrious father, as Scheibe and Birnbaum once debated (see John Lutterman, Early Music America, Summer 2009, pp. 61-4).

I n Wq. 46, the subject enters—the right hand leading the canon—which could have been continued ad infinitum. The momentum that comes from the initial rhythm is not just from the notes’ velocity but also from the accelerated pace of canonical imitation—in other words, speed of fingers begets contrapuntal speed, a kind of organic biomechanical-gestural-psychological cooperation.

A s contrasted with the contrapuntal development of his father J.S., C.P.E.’s cadences are ‘loose’—ambiguous rests of indeterminate length, ambiguous rhythmic cues—suggestive of the physics of superconducting material, or of the physics of superfluidity. C.P.E. lets short-term ‘molecular physics’ of fast-moving harpsichordists’ fingers confront the larger contrapuntal designs and—Surprise!—call the larger designs into question.

I s this Wq. 46 concerto not ultimately a ‘clinical’ piece: C.P.E. Bach, plumbing human neurocognitive pathways of music and emotion? It’s almost as though this C.P.E. Bach composition pre-sages Stockhausen’s controlled aleatory of the later Klavierstücke—a kind of ‘meta-Galant’ style—or maybe instead it reprises the (?) stochastic gestalt of Gregorian plainsong?

T he 11 strings [3-3-2-2-1] and 2 horns have—a priestly role?

W ith the latitude for improvisation afforded by Wq. 46, can we not regard this concerto as a kind of ‘emotional gymnasium’ for esoteric training or ‘tantric exercises’? C.P.E. Bach wants the performers and the audience members to find out how fast can you go from bemusement/humor to pathos, from excited anticipation to ecstatic relief!

I n this connection, the usual sense of ‘frozen’ [scored] improvisations is that the composer was sketching what the performer might do—expecting that the performer would be able, technically, to do what was indicated or readily elaborate on the sketch.

B ut here we have a composer who writes something so demanding that it’s impossible for all but the most elite performer to manage it. Nonetheless, mere mortal performers do attempt it—like firewalkers. Or like pole-vaulters, with stochastically varying degrees of success at vaulting: performing the motoric parts of the Allegro assai of Wq. 46 is like a series of death-defying chasm leaps. We are thrilled to safely land on the opposite side; we are vicariously thrilled when performers do it... the beauty of surviving intact... Is it ‘extreme sport’? Is it a rite?

A nd what about the [runtime] idiosyncrasies of the elite body; or of the musical text/score and its scansion by our human eyes; or of the mechanism of the instrument itself (the plectrum for harpsichord; the bow for strings; the valves/slide for brass; the keys on a woodwind instrument; the laryngeal muscles and flesh of vocal folds). In the case of the harpsichord, the rate of return of the plectrum has relatively high variability (compared to piano, say)… Newtonian physics, in service of transcendent spiritual/emotional experience!

I acknowledge that these are emergent/microgranular sorts of aleatorics that’re not usually considered as ‘proper’ aleatoric forms. They may be either inadvertent (require the participant to ‘let go’ [become indifferent toward self] to enter the altered state of consciousness) or deliberate (require the participant to engage in ritual to induce ecstatic/high-arousal/transcendent state). They may not fit the ‘usual’ definitions, but they’re aleatoric just the same.

T ake, for example, Mozart’s writing in ‘Apollo et Hyacinthus’, where Mozart writes for boy singers (with peri-pubertal changing voices) and creates monumental technical difficulties for them—perilously low ‘alto’ parts for Apollo and Zephyr, especially. Melia and Hyacinth, sopranos; Oebalus, the tenor, for example confronts a technically scary part... a chorus to “sacrifice” on a pyre, then: whose parts Mozart deviously writes so as to expressly conjure a particular emotional state, triggered by events that take place in the recitatives and ‘da capo’ arias. All that.

S o was C.P.E. Bach familiar with tantric and sufi practices? Was Mozart? Were some of their concerti and menuets tantric dance analogues? Were they using aleatoric methods as a way to achieve altered states of consciousness?

E ven if the evidence is too scanty to ever know for sure, ask yourself whether these are sublime incantations with small-scale aleatorics! Ask yourself whether this Wq. 46 union of two harpsichords is an ‘ecstasy of technical plenitude’.

[Musica Antiqua Koln, Andreas Staier, Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46, I, Allegro]

[Musica Antiqua Koln, Andreas Staier, Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46, II, Largo]

[Musica Antiqua Koln, Andreas Staier, Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46, III, Allegro assai]

M y own taste runs more to Gustav Leonhardt’s and Alan Curtis’s or Ton Koopman’s and Tini Mathot’s more ‘over-the-top’ interpretations, I have to admit—compared to the conservative MAK performance. Or maybe the former recordings just happened on occasions of particularly auspicious baroque tantric good luck?

P lenty to discuss with Pamela Fox should she happen to be at BEMF this week…

T The harpsichord is my life... the organ is, in a way, a ‘luxurious extra’ to me.”

— Gustav Leonhardt.

- C.P.E. Bach Complete Works, at Packard Humanities Institute

- C.P.E. Bach Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46 music at Muziekhandel Saul Groen, Amsterdam. [p.9 of 85pp pdf catalogue]

- Festival Centropalia 2009 (Manfred Huss, Haydn Sinfonietta Wien)

- Pamela Fox page at Mary Baldwin College

- Gustav Leonhardt, Alan Curtis & Collegium Aureum. Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46. (Deutsche Harmonia, 1996.)

- Ton Koopman, Tini Mathot & Amsterdam Baroque. Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46. (Wea, 1999.)

- Aleksei Lubimov, Jiri Martynov & Haydn Sinfonietta Wien. Double Concerto for 2 harpsichords, 2 horns, strings & continuo in F major, H. 408, Wq. 46. (VMS, 2007.)

- Aldridge D, Fachner J, eds. Music and Altered States: Consciousness, Transcendence, Therapy and Addictions. Kingsley, 2009.

- Aubert L. The Music of The Other. Ashgate, 2007.

- Bach C.P.E. Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen. Schwickertschen Verlage, 1787.

- Baldock R. Responding to notation. Interpreting dynamic markings in the instrumental music of C.P.E. Bach. Understanding Bach 2008; 3:77-9.

- Becker J. Deep Listeners: Music, Emotion, and Trancing. Indiana Univ, 2004.

- Burkan T. Extreme Spirituality. Council Oak, 2004. (w/ foreword by Andrew Weil MD ?!)

- Cohen D, Dubnov S. in Marc Leman, A. Camurri, eds., Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1317: Music, Gestalt, and Computing. Springer, 1997. Pp. 386-406.

- Cohen D, Wagner N. Concurrence and Nonconcurrence between Learned and Natural Schemata: The Case of J. S. Bach's Saraband in C Minor for Cello Solo. J New Music Research 2000; 29:23-36.

- Fox P. ‘The stylistic anomalies of C.P.E. Bach’s non-constancy,’ in Stephen Clark, ed., C.P.E. Bach Studies, Oxford Univ, 1988, pp. 105ff.

- Greenberg M. Baroque Bodies. Cornell Univ, 2001.

- Helm E. Thematic Catalog of the Works of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Yale Univ, 1989.

- Khan H. The Mysticism of Sound and Music. Shambhala, 1996.

- Knijff J-P. Interview with Gustave Leonhardt. Het Orgel 2000; 96:27-30.

- Kramer R. Unfinished Music. Oxford Univ, 2008. [C.P.E. Bach's style is cited on 78 pages]

- Mirka D. The cadence of Mozart’s cadenzas. Journal of Musicology 2005; 22:292-325.

- Ottenberg H-G. C.P.E. Bach. Oxford Univ, 1987.

- Richards A. The Free Fantasia and the Musical Picturesque. Cambridge Univ, 2006. [C.P.E. Bach's style is cited on 105 pages]

- Rouget G. Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations Between Music and Possession. Univ Chicago, 1985.

- Schneck D, Berger D. The Music Effect: Music Physiology And Clinical Applications. Kingsley, 2006.

- Scolnic V. Pitch organization in aleatoric counterpoint in Lutoslawski's music of the 1960s. PhD Dissertation, Hebrew Univ Jerusalem, 1993.

- Wade R. The keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. PhD Dissertation, 1981.

- Wolff C, et al. Finding the Lost Manuscripts of C.P.E. Bach. Greater Boston Arts, 2001.

- Yearsley D. Bach and the Meanings of Counterpoint. Cambridge Univ, 2008.

T he work is the death mask of its [improvisational] conception.”

— Walter Benjamin.

No comments:

Post a Comment