T he piece starts with a recognizably Mozartean voice, but as different versions of the minuet are superimposed, the textures become complex and passingly dissonant. Soaring themes, too, and bits of poignancy, rise. There’s much to arrest the ear.”

— Scott Cantrell, Dallas Morning News, 21-APR-2006, review of Robert Rodriguez’s ‘Mozart Dice Game’.

A nleitung:S ometime around 1775—when is not known with certainty—Mozart wrote the measures and instructions for a musical compositional method using dice, a table of numbers, and a set of cards. On each card was printed one measure of music and a number to identify that measure. You randomly select from these pre-written measures of music based on rolls of the dice. With each dice roll, you do a table look-up to find out what card (measure) you are to select from the deck. Then you put the cards together to create new Menuets. It was possibly the first [published] algorithmic stochastic composition.

Walzer oder Schleifer mit 2 Würfeln zu componieren,

ohne Musikalisch zu seyn,

noch von der Composition etwas zu verstehen.”

[Instruction:

To compose a waltz or a schleifer / landler with two dice,

without being musically gifted,

nor knowing anything about composition.]

— W.A. Mozart.

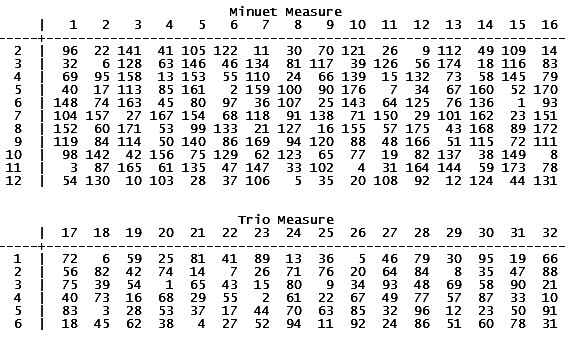

T here are 176 possible Menuet measures and 96 possible Trio measures to choose from. The results of the 32 dice rolls and the pretty large set of pre-written measures give a quite large number of different compositions that could be generated by Mozart’s rules.

B ut there are not 1116 + 616 = 4.6 * 1016 possible compositions as some claim. [My god, there is an error on the internets!]

N or is it 272C32 (176 + 96 things, taken 32 at a time) = 4.6 * 1041 possible menuets.

I nstead, what you have with Mozart’s menuet generator are 1116 * 616 = 1.3 * 1029 possibilities. That’s because his rules specify a menuet as a segmented number (string-vector) comprised of 16 base-11 (undecimal [Babylon5 ‘minbari’]) digits concatenated with 16 base-6 (hexal) digits, where each digit indexes into a separate list of permitted measures. Only members of the specific subset of measures that Mozart enumerated in a given roll’s list are permitted (table column look-ups), not just any from the whole set of all 176 Menuet measures or all 96 Trio measures.

I f you fail to preserve it [the sequence of 32 numbers from your dice rolls, or the sequence of measures you get], it will be a menuet that will [probabilistically speaking—] never be heard again.”

— Martin Gardner, Scientific American, 1970.

- The Menuet section is in the tonic key and the Trio section is in subdominant.

- Measure numbers are indicated in the top row.

- Outcome of each dice roll is indicated in the left-most column (2 to 12 for the Menuet roll with two dice; 1 to 6 for the Trio single-die roll).

- For example, for the first measure (Menuet) if you rolled “snake-eyes” you would play measure #96 of the 176 possible Minuet measures. If in bar 17 (Trio) you rolled a “6” you would play measure #18 of the 96 possible Trio measures.

M usical Dice Game’ begins with the first solo quartet playing the first half of one minuet; both quartets then join to play all eleven versions of those bars at once; the second solo quartet continues with the second half of the minuet, followed by all eleven versions of those bars, again played by all forces simultaneously. Eleven continuous variations follow, based on the harmonies and principal melodic motifs of the original dice game. I most often used the game’s versions for throwing a five, six, eight, nine or, particularly, a seven. Since, by the laws of probability, those numbers are the most likely to be thrown, they have the most melodically distinctive variants. In the first few variations, the themes and harmonies are given in their simple, original forms; then, as the piece progresses, the minuets are disguised, and the music grows more and more chromatic, complex and rhythmically asymmetrical. In the final variation, a synthesis is reached between the Mozartean themes and their transformed versions, as the original minuets return, superimposed over the varied material in a festive musical layer cake.”B eautiful! Having been persuaded/challenged by the DSO to go where angels fear to tread, Rodriguez created a composition guided by Mozart’s stochastic wurfelspiel rules that is notable for its novelty and sheer musicality. It does not have too much emphasis on ‘bar-lines’, despite the ‘measure-wise’ macro-granularity of the stochastic engine (dice-rolling selection of single measures by table look-up). It’s superbly constructed... a moving piece of music in its own right, and one that also invites us to critically rethink Mozart’s own compositional methods and computational composition in general.

— Robert Xavier Rodriguez, score notes, 2005.

I n light of the Schick/ICE Xenakis concert in Chicago earlier this week and my previous CMT post speculating about algorithmic composition methods’ begging for human editing/finishing, I thought I’d mention Mozart’s own experiments, as well as Robert Rodriguez and his Mozart Reloaded.

M usic is meaningless noise unless it touches a receptive mind.”

— Paul Hindemith.

- Rodriguez R. Mozart Dice Game for 2 string quartets. Schirmer, 2005.

- Robert Xavier Rodriguez website

- Mozart Dice Game java source-code at Jmusic

- Online java applet implementation of Mozart Menuet Generator

- Music-without-sound page at Wikipedia (Maximilian Stadler)

- Fields M. GEMS. University of Michigan, 1993.

- Granular synthesis page at Answers.com

- Iturbide M. Les techniques granulares dans la synthèse sonore. PhD dissertation, Univ Paris VIII, 1999.

- Shiflet A. Musical notes. College Math Journal 1988; 19:345-7.

P otential for banality, or beauty

What are avatars of impendingness?

After Verdi died in 1901 (January, in Milan, of complications from a single, deterministic stroke), Italy suffered a cardiac/cultural arrest of confidence.

After Xenakis died in 2001 (February, in Paris, of complications from multiple stochastic ailments he had been enduring), Greece suffered nothing, at least not right away.

But soon after each event, the protean exuberance of the respective century collapsed; emergent self-absorption papered over with frenzied ornamentation.

No such country as “Homeland”... non-existence hardly ameliorates its artistic self-glorification.

You know, things that happen according to Markovian rules can be changed without loss of overall meaning, and likewise without gain of overall meaning.

What are Markov melody engines?

Stochastic algorithms who have had a recurring, salacious role in western music composition for more than 200 years...

Who do not want the listener to be aware of their forms and metabolisms.

Mozart’s ‘Musikalisches Wurfelspiel’ K.516f is well-known. But other composers, including Haydn and C.P.E. Bach, fooled around here.

Recombining humanly-composed motifs in random orders, first for the novelty of it, but then as friends/accomplices, then as crutches/co-dependents, and finally as addictions.

Mozart wrote (or [at least] Peter Welcker published in 1775, in London) a ‘Tabular System Whereby Any Person without the Least Knowledge of Musick May Compose Ten Thousand Different Menuets in the Most Pleasing and Correct Manner’.

‘Pleasing’, maybe, sometimes. ‘Correct’, leave it for the first violin to say.”

No comments:

Post a Comment