T he effect of the economic downturn is already pronounced—in terms of our subscription sales and attendance so far this season, and in terms of corporate and foundation money. I wonder whether, if we merged with the other main chamber music organization in our city, we might do better overall. The reason I think the answer may be ‘yes’ is that our respective programs tend time and again to collide with and compete against each other for the same audience. For example, two pianists in one week--the other org’s program on Friday night, ours on Saturday night. Or two early music programs within a fortnight. The ‘supply’ [of chamber music programs] exceeds the ‘demand’ in our market area, or at least exceeds our audience members’ monthly budgets of time and money. CMT sometimes has spreadsheets and math [to illustrate how some process works or to provide a tool to help CMT readers’ decision-making]. Could you do something in Excel to show whether there would be financial advantages or disadvantages if we combined with our competitor? The assumptions would be that we would have the same number of events each season [Presenter P’s events + Rival R’s events]; the prices and expenses would be the same [P + R roll-up]; the staff would be the same [P + R, with executive co-directors and artistic co-directors]; and the corporate and foundation funding would be the same [P + R]. If we merged, we would just coordinate our programs to not compete—to more efficiently and effectively serve the demand in our community. Possible?”The performing arts market is tremendously fragmented. That fragmentation inevitably leads to inefficiencies. There are more than 520 presenter entities who are organizational members of Chamber Music America. And one thing that’s clear from examining CMA’s directory of chamber music presenters is that communities in the U.S. that have performing arts markets that are robust enough to have one presenter tend in fact to have two or more chamber music presenters. In many cases, that means that there is relatively intense competition for what is almost certainly a finite market—a finite monthly or quarterly consumer spend per household. Probably the same is also true in cities in Europe and the U.K.

— Anonymous.

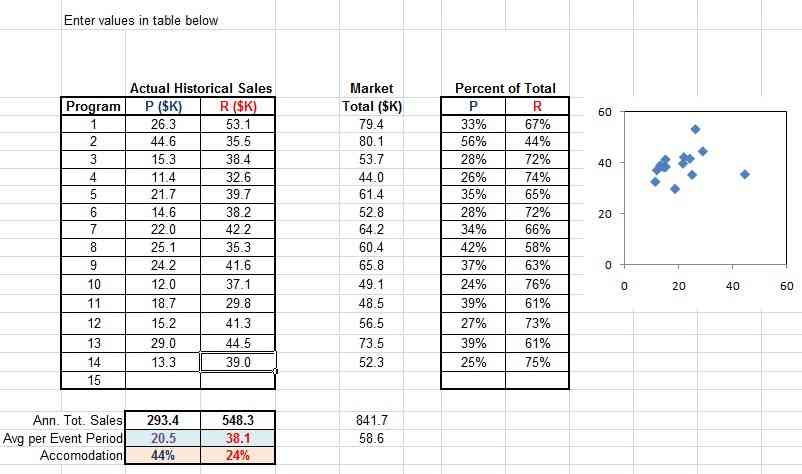

For simplicity and to directly respond to the anonymous emailer’s question, I’ve put together a mathematical model that is for two competitors in a market—a duopoly. It would be far more complex to create an accurate, actionable financial merger model for three or more competitors. Actually, if the proposition were to simultaneously consolidate three or more competitors into one unified presenter organization, then you could still use this Cournot-Nash game-theory model as-is. You would simply put your own figures in as Presenter P, and then sum the figures for all of your competitors and put those sums in the Rival R column.

Basically, you need the ticket sales (earned income) figures for you and your competitor for last season's events—not the ticket drop numbers (with comp tickets and other imponderables) but the cash money taken in. You can exclude the events that each of your orgs produced that did not compete with each other at all—because they were far enough apart (say, more than 4 weeks) so that it’s implausible that a potential audience member would’ve decided to decline to attend your event because they were already attending your competitor’s event, or vice versa. Then you adjust the up-down arrows so that the accomodation figures match your last-season historical values, and so that the Cournot-Nash duopoly figures on the left more or less match the last-season actual average per event period figures on the lower right. (Just click on either of the screen-shot images below to Open or Save_as the Excel spreadsheet.)

Program ‘event periods’ means any interval of time during which the competitors’ programs compete against each other for consumers’ dollars. It doesn’t have to mean conflicting events on the exact same dates. It may be events on adjacent dates, such that attendees who otherwise would like to attend both programs probably will not buy tickets and attend chamber music concerts on two consecutive days. It may be events during the same week or fortnight, with the same criterion that most members of the target market may not attend two or more chamber music events within, say, 10 days of each other.

There are a number of assumptions and limitations of this simple Cournot-Nash model of financial competition:

- It doesn’t take into account the possibility of ‘curvature’ of the elasticity of demand;

- It ‘linearizes’ the [possibly non-linear] competitive interaction;

- It uses the statistical covariance cov(P,R) between the competitors as the measure of the ‘accomodation’ effect of the sales of one presenter on the competitor’s sales, which, while simple, may be a far-from-ideal metric of the competitive economic interaction between the two;

- It doesn't account for potential greater-than-additive ‘synergies’ in terms of induced greater demand or brand-recognition or marketing effectiveness that a merged entity might achieve;

With the insights you glean from playing around with this simple model, perhaps you will try to arrange your programming timing and content so as to minimize the numeric value (covariance) of your own ‘accomodation’ to your competitors—i.e., select your artists and programs so as to make your own ticket sales very insensitive to the programming that your competitors present, while simultaneously maintaining your ‘brand’ and maximizing the demand for the programs you select and book.

This simple model can be used to devise other strategies: to make your organization attractive for a merger or, conversely, to make your organization an unattractive target (by removing any appearance of financial advantage associated with combining and coordinating programming so as not to compete). ‘Accomodation’ values that are large (> 40% for one or both competitors) tend to predict financial gains for a merged entity that are upwards of 30% compared to the total annual sales with each competitor separate. Conversely, ‘accomodation’ values that are low (< 10% for one or both competitors) tend to predict that merging the competitors would not net much income growth for the merged entity—growth of 15% or less.

So please have a look at the model. Send me email or comment on it if you wish. And give us your thoughts in the poll that’s embedded in this post. (Note: Your participation in the online poll does not disclose your own identity or your organization’s identity, nor does it reveal anything about your community. It does not collect information other than which selection you click on.) Thank you!

- Andreff W, Szymanski S, eds. Handbook on the Economics of Sport. Elgar, 2007.

- Chen S-H. Evolutionary Computation in Economics and Finance. Physica Verlag, 2002.

- Cornuejols G, Tutuncu R. Optimization Methods in Finance. Cambridge Univ, 2007.

- Cowan R, Jonard N, eds. Heterogenous Agents, Interactions and Economic Performance. Springer, 2002.

- van Damme E. Stability and Perfection of Nash Equilibria. 2e. Springer, 2002.

- Fisher T. Managerial Economics: A Game Theoretic Approach. Routledge, 2002.

- Kolm S-C, Ythier J, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity, Volume 2: Applications. North Holland, 2006.

- Lambertini L, ed. The Economics of Vertically Differentiated Markets. Elgar, 2006.

- Neubecker L. Strategic Competition in Oligopolies with Fluctuating Demand. Springer, 2006.

- Nowak A, Szajowski K, eds. Advances in Dynamic Games: Applications to Economics, Finance, Optimization, and Stochastic Control. Birkhauser, 2004.

- Plott C, Smith V, eds. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, Volume 1. North Holland, 2008.

- Salvatore D. Managerial Economics in a Global Economy. Oxford Univ, 2006.

- Smith V. Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological Forms. Cambridge Univ, 2007.

- DSM. Non-profit chamber music orgs and the recession. CMT blog, 17-JUL-2008.

- DSM. Chamber music economics: Divisibility of time and the Monty Hall problem. CMT blog, 10-APR-2008.

- DSM. Few chamber orchestras are too big to fail: Market size, scale and sustainability. CMT blog, 30-MAR-2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment