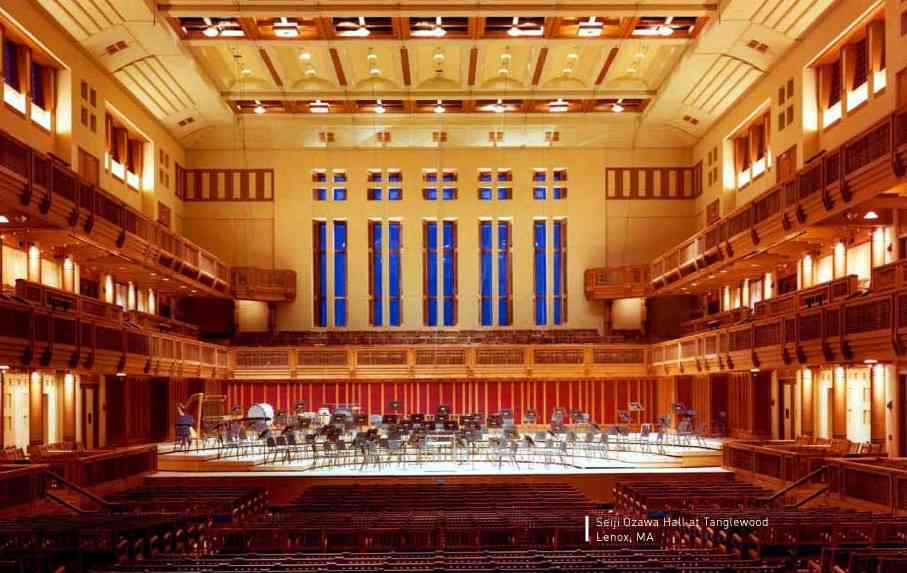

H ow are we to build emotional expression into music criticism? The new way is not to amplify criticism by adding interpretation to analysis but, rather, by amplifying analysis itself. For once one ceases to see expressive properties of music as semantic or representational properties, it becomes clear that they are simply musical properties ... and as such a proper subject of musical analysis.”The BSO’s Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood (Elliott Carter Centenary) on Tuesday had a diverse program of smaller pieces representing various phases of Carter’s career, performed by members of the New Fromm ensemble.

— Peter Kivy, Fine Art of Repetition, p. 316.

- Enchanted Preludes

- Figment I

- Figment II

- Esprit doux I & II

- Au Quai [To the quay; quant ‘à [pour-]quoi’ c’est que nous allons ‘au quai’ je ne savons pas. Pour découvrir un mot français ironique?]

- Trilogy

- Two Thoughts about the Piano (Intermittences; Caténaires)

Each of the pieces epitomizes the narrative and intimate dialogical idiom of chamber music. And each calls into question the conventional dictum that musical dialogue lacks specific semantic reference to the external world. Here, for example, ‘Caténaires’ has phrase-structure and lines between left-hand and right-hand that are clearly arcs—representational of curves draped in mid-air, in some parts with descender cables attached to the pylon-to-pylon catenaries, such as we see in bridge designs. You do not need to see the title of the piece to have the clear impression of the pendency, the evocation of gravity creating catenary curves in pendant strands.

Representational acoustic art! Pianist Sandra Gu performed this with intensity and grace. Likewise, ‘Intermittences’, performed with much feeling by pianist Jacob Rhodebeck, is an exposition of intermittent effects and an extended meditation on human expectations—the decay of notes once struck; the reverberation and decay in the Hall; the intermittency of rhythms, of textures, of harmonies that come, go, and reappear. We anticipate things as we do, for reasons we don’t fully understand. Carter’s ‘Two Thoughts about the Piano’ helps us not only to understand the instrument and the character of pianists who express themselves through it, but also helps us to understand ourselves—and our relations to those pianists, the composer, and the music.

Representational acoustic art! Pianist Sandra Gu performed this with intensity and grace. Likewise, ‘Intermittences’, performed with much feeling by pianist Jacob Rhodebeck, is an exposition of intermittent effects and an extended meditation on human expectations—the decay of notes once struck; the reverberation and decay in the Hall; the intermittency of rhythms, of textures, of harmonies that come, go, and reappear. We anticipate things as we do, for reasons we don’t fully understand. Carter’s ‘Two Thoughts about the Piano’ helps us not only to understand the instrument and the character of pianists who express themselves through it, but also helps us to understand ourselves—and our relations to those pianists, the composer, and the music.The music on Tuesday’s program was full of internal references, linkages, and interactions among individual segments, lines, and parts. ‘Trilogy’ (Nick Stovall, oboe, and Megan Levin, harp), ‘Enchanted Preludes’ (Brook Ferguson, flute, and David Gerstein, cello), and ‘Esprit doux’ (Brook Ferguson, flute; Brent Besner, clarinet; Nick Tolle, marimba) are, essentially, reflection pieces on musical segmentation.

We listen and answer these questions:

- Do individual segments form primarily within one part or across two or more?

- Do associations among segments develop within a part or between parts?

- How many distinct streams of association are active simultaneously?

- How do the segments, associations, and streams evolve over time?

In these Carter pieces there are diverse changes in the segmentation. These changes in segmentation are vehicles for changing modes of interaction among the parts. In ‘Esprit doux’, the dialogue between the clarinet and flute gives way to the trio section, in which the marimba is not so much a co-equal voice as it is an omniscient narrator—functioning much as the piano part often does in piano trios. The marimba ‘explains’ the context within which the segmentation and trill-swapping exchanges between the flute and clarinet parts makes ‘sense’.

We get what amounts to a series of shifts from individualism to ensemble collectivism, and from predominantly contrapuntal textures to predominantly harmonic textures. In the duets and trio, the interplay among individual personae is internal to the group. In the solo pieces (Figments I & II; Two Thoughts), the interplay references the soloist’s relation to the external world.

Figment I, with its double-stopped figures, one note held constant and the other sliding up in pitch, evokes things suspected and feared true. It is the essence of anxiety, distilled. It conveys ‘anxiety-as-process’, not as ‘symptom’. Anxiety (and the troubling figments of imagination that accompany it) is, you see, not a ‘state’ or ‘condition’ but a succession of thoughts and events that, together, comprise the anxious self—alienated from comforts and reassurances, isolated existentially. Segmentation in the cello part, superbly played by Kathryn Bates, propels our understanding this existential discomfort. Beautiful, iconic, elegant, credible.

Have a look at Peter Kivy’s books, for detailed discussions of texuality and the limits of the representational in music—not in Elliott Carter’s music per se, although Carter’s music does illustrate or embody many of Peter’s arguments.

- BSO Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music

- Carter page at Classical.net

- Carter Centenary website

- Kozinn A. Blogging at Tanglewood on NYT ArtsBeat.

- William Rawn Associates Architects, Inc

- DeBellis M. The representational content of musical experience. Philos & Phenomenol Res 1991; 51: 303-24.

- Juslin P, Sloboda J, eds. Music and Emotion. Oxford Univ, 2001.

- Peter Kivy page at Rutgers Univ

- Kivy P. Music Alone: Philosophical Reflections on the Purely Musical Experience. Cornell Univ, 1991.

- Kivy P. The Fine Art of Repetition: Essays in the Philosophy of Music. Cambridge Univ, 1993.

- Pople A, ed. Theory, Analysis, and Meaning in Music. Cambridge Univ, 2006.

I love Elliott, but I loved his music first. (I can’t do this in reverse; I can’t love the music just based on a rapport with the composer.)”

— Conductor James Levine.

No comments:

Post a Comment