E ven in the first five quartets Bartók remains elusive. One might assume that he possessed something of Yeats’s power to develop continuously, and that this is revealed in his tireless revision of his means of self-expression—but what was he trying to express? One feels in late Beethoven, as in late Mozart, that certain changes in technique reflect a change of temperament, a deepening, a serenity which, in Mozart’s case, gives the music a kind of weight without changing its basic quality of gaiety. But it is not this quality that distinguishes [Bartók]... Bartók struck most of the people who met him as a curiously inexpressive person—remote and aloof. As a small boy he had a skin disease that covered him with sores for six years. During this time he was so ashamed of his appearance that he felt at ease only with his mother. The disease ultimately disappeared. But instead of becoming less introverted, Bartók spent his nights worrying that it might come back... [Bartók was diagnosed with leukemia in 1941, and died of complications of this 4 years later.] The story strikes a Proustian note: it is clear from the beginning that Bartok is one of those with a basic mistrust of life and a desire to retreat into some inner world... ”

— Colin Wilson, p. 87.

W e human beings are governed by the urge to conform and blend in with our surroundings. We follow fashion. We become part of cultures of conformity—religious communities, military groups, sports teams. We take on corporate identities. Likewise, we seem to have the capacity to grow into our built environment, to familiarize ourselves with it, and eventually to find ourselves at home there. We have a chameleon-like urge to adapt, and, given the increasing mobility of contemporary life, we are constantly having to do so. The desire for camouflage is a desire to feel connected—to find our place in the world and to feel at home.”The defining quality in Bartók’s Rhapsody No. 2 for Violin and Piano (1928; revised 1945) is its elusiveness. Hiding the simplicity and forthrightness of Hungarian rural culture within the refined modalities of urban art-music—this is inherent in Bartók’s compositional methods in many of his pieces. And in fact disguising and embedding like this are done by Kodàly and Grieg and Brahms and many other ethnomusicologist-composers, too. But this Rhapsody embodies camouflage of a deeper, psychological sort.

— Neil Leach.

We know from his correspondence and various biographical materials that Bartók was unsatisfied with the metropolitan ethos and urban aesthetics, and this dissatisfaction imbued Bartók’s writing with a highly personalized, proletarian politics.

Of course, folksong transcriptions involve compromises. Faithfulness to their cultural meaning depends on the extent to which the ‘other’ is bestowed with power in the transcription/adaptation. Mere empathy in the musical treatment of the folk idiom is not sufficient; there has to be moral standing and respect and power.

But this Rhapsody subverts its own folk-derived character and its character as a ‘work’ and as an object of dispassionate reflection. Instead, it propels the performer/listener to a new level of active subjectivity. The composer embarks on what amounts to a manifesto for the performers/listeners, about the rules of representation. The piece is not a ‘conversation,’ and it isn’t about what exactly is ‘represented’. It’s violinist and pianist presenting a united-front polemic regarding representation itself: what it is to represent reality and ‘self’ in music. And this inevitably hinges on what is or is not accessible to our senses—and on the fallibility of our senses. How do we know what is ‘real’? How do we know who is Bartók? He eludes us.

A reception aesthetics calls into question one of the central tenets of analysis—the stability of the work’s identity, its capacity to make its own statement independent of any recognitional condition. Ultimately it calls into question the very possibility of an ontological essence for the musical work.”

— Jim Samson, in Cook & Everist, p. 44.

In order to emphasize the quasi-rustic character of the music, Bartók devised ways of blurring demarcations between lines, imparting a faux country ‘roughness’ to them. He devised novel uses of glissandi, lending a throw-down impartiality between the violin and piano parts that dissuades the listener from looking for additional potentially-discorroborating evidence. By sliding the melodic line from one note to the next at the right instants, Bartók conceals the thematic contours and creates the illusion that the piano is ‘merely’ handling the melodic line from the violin. In other words, Bartók uses deceptive musical contours to camouflage personal identities in the complex musical layers. Why else would the glissandi be temporally staggered as they are? The perfect execution of these tightly interconnected glissandi requires an extraordinary level of control in tempi and balance between the violinist and the pianist—and it is a huge challenge to “pull it off”.

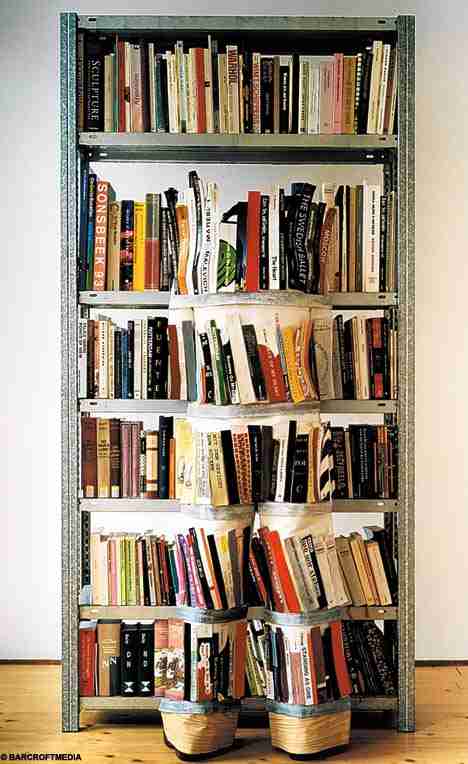

Spot the ‘invisible’ men and women in artist’s amazing photographs. Daily Mail, 24-FEB-2008.

[ Desireé Palmen, a 44-year-old Dutch artist, stages trompe l’oeil scenes using traditional ‘analog’ methods. She photographs a scene without people in it and replicates portions of these images on clothing by hand. She then has people put on the clothing and carefully poses her subjects in the previously-photographed background scene. ]

I ’d like people to consider what it means to let the government control our daily lives [with intrusive surveillance, erosion of privacy, and coercive technology]. When we are controlled we hand over our individual responsibilities to the state. I wanted to make a suit for the non-criminal citizen whose house is being watched 24 hours by street surveillance cameras. I’m also responding [to a progressively more prevalent wish that ordinary people have] to disappear [and regain their privacy and dignity].”

— Desireé Palmen, 2008.

Some years ago, Edward Said showed how musical form asserts itself on important issues of social justice—his analysis of Beethoven’s opera, Fidelio, where Florestan, the hero, undergoes ‘extraordinary rendition’ and imprisonment without trial. Florestan’s silence, Said says, embodies a European conception of the politics of silence, where silence socially has been associated with alienation and with recrimination, and where musically it relies on an historical relationship between sound and silence that back-handedly acknowledges the existence of the Other, acknowledges the existence of what is hidden or denied through silence. That’s the kind of evasion that I hear in this Rhapsody No. 2.

W hen Florestan is imprisoned for speaking an unacceptable truth, we are to suppose ... that he was once able to speak the truth, and then he was buried in a silent dungeon for having done so. What are we to make of other notions of silence: the case of someone already invisible and unable to speak at all for political reasons, someone who has been silenced because what he or she might represent is a scandal that undermines existing institutions?”

— Edward Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, 2000, p. 521.

But one can be really silent, and one can be pseudo-silent. The camouflage or ‘disruptive-pattern material’ (DPM) in this Rhapsody seems to manifest—What?—Bartók’s opposition to esotericism? his concurrent and paradoxical wish for privacy at the same time that he desired a more satisfying sense of ‘belonging’? his vehement response to intrusive governments in his own day? He challenges us to try and find him, but he exerts himself to elude us. He increases the musical complexity, much as current encryption and stego software techniques do when attempting to foil automated steganographic detection/decryption.

Basically, the Hungarian gypsy folk idioms are the nominal ‘scene’ within which the real identities of violinist and pianist and composer are made to dissolve. This work is a standard, two-part Hungarian rhapsody, with a slow opening and enthusiastic folk music gestures, culminating in a high-velocity, virtuosic conclusion. Bartók wrote rustic rural folk sounds throughout. The violin part—chock-full as it is with florid ornaments, trills, and double-stops—might be thought to’ve been designed to bring out the player’s personality, and indeed that’s the chief temptation. But the part’s complexities are more virtuosic obfuscations and fictions than opportunities for matter-of-fact personal revelations.

When this piece is performed without respect for Bartók’s intentions, we hear the personalities of the violinist and the pianist who are in front of us, alive in 2008, in plain-text and undisguised. But when Rhapsody No. 2 is played particularly well, we hear a convincing mid-Century Hungarian illusion, a convincing deception. Surveillance—of the players, of the composer, of the listeners—is futile, and coercion impossible. Confidentiality and privacy remain protected.

W arfare has changed in the same ways as the composition of pictures... War has become anonymous and now renounces the desire for show.”James Ehnes and Andrew Armstrong will perform Béla Bartók’s Rhapsody No. 2 for Violin & Piano and other works this coming Saturday, 01-MAR-2008, in Kansas City. We look forward to trying to unwrap Bartók’s beautiful enigma. At the very least, we look forward to vicariously concealing ourselves in plain sight, in the pungent folk-music extroversions of introverted Hungarian diaspora.

— Pablo Picasso, 1944, on improving camouflage, letter to Apollinaire, quoted in Belting, p. 336.

G ilroy’s notion of ‘changing same,’ in which reiteration ‘is not some invariant essence that gets enclosed subsequently in a shape-shifting exterior [nor is it …] the sign of an unbroken, integral inside protected by a camouflaged husk.’ [It] is conducive to the dynamic, complex movement that Gilroy deems essential for formation of diaspora.”

— Cameron Bushnell, Univ Maryland PhD Dissertation, 2007, p. 118.

- James Ehnes website

- Albrecht G. Memories of Rain. 2004.

- Attali J. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Univ Minnesota, 1989.

- Behrens R. False Colors: Art, Design and Modern Camouflage. Bobolink, 2002.

- Belting H. The Invisible Masterpiece. Univ Chicago, 2001.

- Blechman H, Newman A, eds. Disruptive Pattern Material: An Encyclopedia of Camouflage. Firefly, 2004.

- Bogue R. Deleuze on Music, Painting, and the Arts. Routledge, 2005.

- Botstein L. Listening through reading: musical literacy and the concert audience. 19th-Century Music 1992; 16:137-55.

- Bull M, Back L, eds. The Auditory Culture Reader. Berg, 2003.

- Chipman A. Loneliness and liberation in the life and stage works of Bela Bartok. Psychoanal Rev. 2004; 91:663-81.

- Cooper D. The unfolding of tonality in the music of Béla Bartók. Music Analysis 1998; 17:21-38.

- David C. The Beauty of Gesture: The Invisible Keyboard of Piano. North Atlantic, 1996.

- Gillies M. Bartók: His Life and Works. Oxford Univ, 2009.

- Gilroy P. Against Race: Imagining Political Culture Beyond the Color Line. Harvard Univ, 2000, p. 129.

- Gollin E. Multi-aggregate cycles and multi-aggregate serial techniques in the music of Béla Bartók. Music Theory Spectrum 2007; 29: 143–76.

- Johnson N, Duric Z, Jajodia S. Information Hiding: Steganography and Watermarking - Attacks and Countermeasures. Springer, 2000.

- Kerman J. Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology. Harvard Univ, 2006.

- Kerman J. Write All These Down: Essays on Music. Univ California, 1998.

- Kipper G. Investigator's Guide to Steganography. Auerbach, 2003.

- Korsyn K. Decentering Music: A Critique of Contemporary Musical Research. Oxford Univ, 2004.

- Lapidaki E. Learning from masters of music creativity. Phil Music Educ Review 2007; 15:93-117.

- Leach N. Camouflage. MIT, 2006.

- Martens F. Violin Mastery: Talks with Master Violinists and Teachers. Bibliobazaar, 2007.

- McTiernan J. Predator. (20th-Century Fox, 1987.)

- Michaux J. Medical folder of Béla Bartók. Bull Mem Acad R Med Belg. 2006; 161:171-80.

- Michaux J. The solitude of Bartók: a hidden life. Bull Mem Acad R Med Belg. 2005; 160:311-8.

- NYT. The ebb and flow of movies. Graphic, 23-FEB-2008. (camo trend pattern, with area and height denoting cumulative-gross and per-week-gross)

- Provos N, Honeyman P. Detecting steganographic content on the internet. Univ Michigan, CITI Tech Rpt, 2001. [1MB pdf]

- Said E. Musical Elaborations. Columbia Univ, 1991.

- Said E. 'From Silence to Sound and Back Again.' Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Harvard Univ, 2000, pp. 507-26.

- SARC StegAlyzerSS software

- Schneider D. Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality. Univ California, 2006.

- Shih F. Digital Watermarking and Steganography: Fundamentals and Techniques. CRC, 2007.

- Solie R, ed. Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship. Univ California, 1995.

- Steganography page on Wikipedia

- Suchoff B. Béla Bartók: Life and Work. Scarecrow, 2002.

- Tufte E. Beautiful Evidence. Graphics, 2006.

- Whittall A. Autonomy/heteronomy: Contexts of musicology, in Cook N, Everist M, eds. Rethinking Music. Oxford Univ, 1999, pp. 73-101.

- Wilson C. Chords & Discords: Purely Personal Opinions on Music. Crown, 1966.

- Wilson P. The Music of Béla Bartók. Yale Univ, 1992.

W hat these suppositions together come to is a denial that composers need or want accurate information about music, at least some of the time. Indeed, a more extreme account of the vocational difference wout have it that an occasional outright falsehood may be of use to the composer, even though believing it would be beneath the theorist. This view might leave room for a special discourse that might be called ‘compositional theory’ in a gesture of indulgence to those whose activities depend on occasional self-deception. These ideas seem dubious to me; it is not easy to understand how they can enjoy the credence that the undeniably do in some quarters of our musical culture. Beyond this, I feel obliged to say such ideas are offensive to me: taken to their logical end, they make me out to be too intellectually concerned to be a real composer, yet too uncritical to be a real scholar... Imagine walking in on Beethoven at work. He tapes middle D# a few times on his piano, with evident interest and perhaps a trace of amusement. You can’t hear anything amusing in his D#s, though. In fact, you can’t hear much of anything at all in them. Obviously Beethoven has something in mind that you don’t, that lets him hear something in his D#s that you can’t. What does he have in mind?”

— Joseph Dubiel, in Cook & Everist, p. 264.

No comments:

Post a Comment