W ould you agree that the difference is a near-horizontal rear forearm, subsequently maintaining the connection with the shoulders? I think a more vertical forearm is a result of keeping tension in the rear-most scapula. I believe that these players are actually loading their scap’ in such a way that their elbow moves into a more ‘slotting’ position. The reason they maintain connection is because they maintain the ‘scap load’ and let the rotation take their hands/bat to the ball. In some of these drills, the vertical forearm is a checkpoint or even a ‘cue’ to get the young player to maintain some scap’ tension, which prevents disconnection and excessive external rotation of the shoulder/upper arm.”Viola da gamba bowing biomechanics is quite a bit different from bowing members of the violin family. For one thing, the under-handed way of holding the bow means that the wrist and forearm have fewer (remaining) degrees of freedom and less range of motion, compared to over-handed violin bowing. And the dorsal flexion of the arm—and supination/rotation of the forearm—to hold the viola da gamba bow put more emphasis on the strength and agility of the supraspinatus. With that in mind, CMT readers who’ve asked about viola da gamba bowing and strengthening exercises may find some of the sports medicine and rehab links below useful. Especially ones that are involved in épée fencing.

— Anonymous sports medicine physician, discussing biomechanics of baseball arm motions.

Why? With an underhanded bow hold, much of the work is done with the forearm opening from the elbow, with little shoulder and upper arm. The elbow contributes far more with an underhanded grip than it does overhanded.

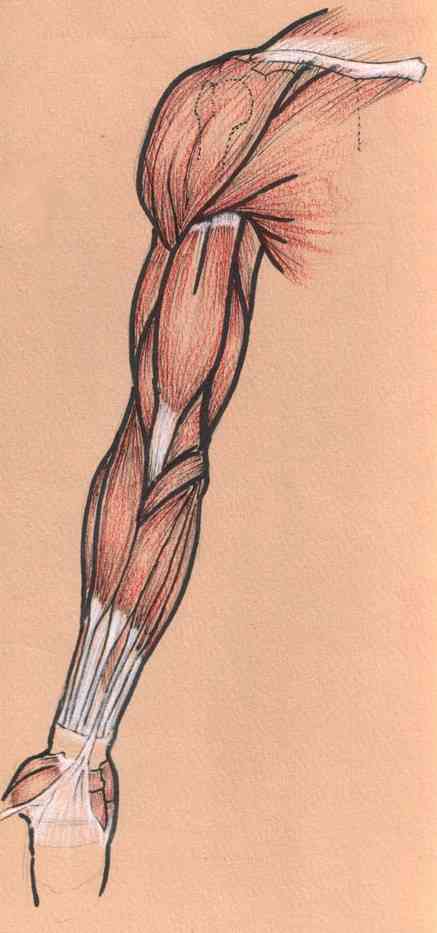

You may find that a good bit of the sports medicine literature on ‘rotator cuff’ is germane to viola da gamba bowing performance as well. (The rotator cuff is made up of four muscles: subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and the teres minor. The rotator cuff muscles work as dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder girdle. In all, there are 30 muscles providing movement and support for the shoulder: 15 muscles move and stabilize the scapula; 9 muscles provide for glenohumeral joint motion; and 6 support the scapula on the thorax. Supraspinatus and other muscles of the ‘rotator cuff’ are just a few elements of the intricate shoulder anatomy.)

I’d say that the ‘stretch reflex’ probably does matter in viola da gamba bowing. But its importance in the ‘ballistic’ context of rapid bowing passages is probably small—see J Appl Biomechanics 1997, volume 13, fascicle 4, for example. But, for typical gamba passages with backbow-forwardbow abduction-adduction of the scapular complex happening at moderate velocities: that’s where proprioception—the stretch reflex—would be most important in control of muscles moving the bow. Rotator muscles surrounding the glenohumeral joint—the muscles involved in external rotation of the arm/elbow—probably not too important in rapid bowing. Instead, it’s the scapula that’s dominant in terms of mechanical linkage of the bow to the body. And the degree of elbow flexion—how close to horizontal the right forearm is—affects how much the ‘stretch reflex’ around the elbow can then contribute to the biomechanics of the bowing muscles’ performance.

Gonzalez and coworkers have shown how activity of muscles that cross the ‘elbow joint complex’ (EJC) is affected by forearm position and forearm movement during elbow flexion/extension. They developed a three-dimensional musculotendinoskeletal computer model of multiple-degree-of-freedom (df) rapid (ballistic) elbow movements to study this. The model demonstrated how changes in forearm position mostly affected the flexor muscles, far more than the extensor muscles. The model also indicated that, for specific 1-df and 2-df movements, activating a muscle that is antagonistic or noncontributory to the movement can significantly reduce the movement time. The up-shot is that good muscle tone from moderate strength training likely improves viola da gamba bowing speed and accuracy.

I f you begin with a backbow (‘roverso’), then you must be prepared also to keep the same consistent alternation of back and forward bows. Practice both ways, so that you are not caught unawares and are unable to straighten out the bowing in a fast passage. A fast run that begins off the beat must start with ‘roverso’ while a similar passage beginning on the beat would start with ‘dritto’. If you have a sequence of ‘groppetti’ [English seventeenth century theorists would call them ‘relishes’ or ‘double relishes’ –Ian Gammie] then begin the first on a forward bow, take the next on a back bow etc.”

— Sylvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, 1542, Book I, Chapter 6 (quoted in Gammie I, Chelys 1978; 8:23-30).

T he bow is to be held with thumb, middle and fore-finger. The thumb and middle finger hold the bow so that it does not fall, the index finger applies greater or lesser pressure on the strings as is required. [This would preclude having a finger on the hair of the bow, as was common practice in the seventeenth century, and the articulation and volume is to be controlled through the stick instead. There has been some confusion in modern times over what Ganassi meant precisely with his description of the fingers. I consider it unlikely that he meant a player to have the index finger on the hair while the thumb and middle finger hold the stick—an unusual physical contortion at the very least. Ganassi intends that the index finger should apply pressure to the strings of the viol, not to the strings or hairs of the bow. –Ian Gammie] The bow should be placed about four finger widths from the bridge—depending of course on the size of the instrument, the arm relaxed, the hand firm but not tense, so as to draw a clear and pure sound from the viol. Playing closer to the bridge will give a rougher tone, playing nearer to the finger-board will give a softer, sweeter tone.”

— Sylvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, 1542, Book I, Chapter 6 (quoted in Gammie I, Chelys 1978; 8:23-30).

What else? Besides external rotation and dorsal flexion of the right arm, viola da gamba playing involves a lot of inferior abduction for backbowing and inferior adduction for the forwardbow. The deltoid is an ‘obvious’ abductor of the arm, but the deltoid is not an effective abductor unless the supraspinatus muscle helps. The deltoid alone tends to press the head of the humerus up under the acromion process; but the supraspinatus has also to do considerable work in viola da gamba bowing, at least in the more energetic passages. In terms of exercises, you will want to devise a ‘balanced’ program, to strengthen all of the relevant shoulder muscles. Some of the links below are good resources to help you discover an exercise program that’s right for you, to strengthen and tone these muscles.

Most gamba players think it best to use the terms forwardbow or backbow for viola da gamba bowing, and these terms honor the predominant biomechanics of the arm in proper gamba bowing technique. Understandably, some players or teachers who play viols as well as violins may say upbow and downbow, out of habit. But those terms tend to evoke kinesthetic mental images that may distort the idea of what a proper gamba bowing technic would be.

There are aspects of melodic and rhythmic elements of the Baroque viola da gamba repertoire—the long, arching polyphonic lines of the ricercar; of punctuated Italian canzoni; of the dramatic madrigal style—that challenge the player’s shoulder differently than, say, classical violin repertoire. The viola da gamba requires a fluid control of the melodic and rhythmic elements. Rapid excursions to distant registers require a smooth technic that belies the intricacy of the writing. In other words, the biomechanics of virtuosic viola da gamba performance is substantially different from the biomechanics of virtuosic violin performance—not just because of the differences in elevation of the right arm, but also because of the kinematic implications of the gamba repertoire.

In summary, unlike the violin family, the upbow is the stronger motion for viola da gamba, not the downbow. The supraspinatus is often a main source of trouble, just as it may be for baseball players, but the complexity of the shoulder anatomy makes it impossible to say, without physically examining you, whether that is the issue or the only issue in your case. The best thing is to schedule yourself a consultation with an orthopedist, a sports medicine physician, or a physical medicine physician. Or maybe a fencing instructor?

- Prof. Catharina Meints, Strings Dept., Oberlin Conservatory

- Oberlin Historical Performance curriculum

- ClassicalFencing.com

- ShoulderDoc.co.uk

- ShoulderPainInfo.com

- PrimalPictures.com graphics package

- PrimalPictures.com sports injuries [1MB mov]

- PaulManley.co.uk

- Viola da Gamba.org

- Australian Viola da Gamba Society website

- Loulie page at Viola da Gamba.org

- Viola da Gamba Society of America.org

- Gamba bowing video [10.2 MB mp4]

- Viola da Gamba Society of America Conclave

- Viola da Gamba Society of New England

- Viola da Gamba.com

- Viola da Gamba books

- Ruby Viola da Gamba

- Dunford website

- Ashmead website

- HFG website

- Historical Bows website

- CF website

- l'Abbat M. The Art of Fencing, or, The Use of the Small Sword. Dodo, 2007.

- ACSM. Resources for the Personal Trainer: Techniques, Complications, and Management. Lippincott, 2006.

- Barth B, Beck E, eds. Complete Guide to Fencing. Meyer & Meyer Fachverlag und Buchhandel, 2006.

- Behnke R. Kinetic Anatomy. HumanKinetics, 2006.

- Bowden B, Bowden J. An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles. Morton, 2002.

- Breteler K, Spoor C, Van der Helm F. Measuring muscle and joint geometry parameters of a shoulder for modelling purposes. J Biomechanics 1999; 32: 1191-7.

- Brindle T, Nyland J, Shapiro R, Caborn D, Stine R. Shoulder proprioception: latent muscle reaction times. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999; 31: 1394-8.

- Bylsma A. Bach, The Fencing Master. 2e. Fencing Mail Basel, 2001.

- Cheris E. Fencing Steps to Success. HumanKinetics, 2001.

- Cherry B. Shoulder Rehab Exercises. MTSU, 2002.

- De Luca C, Forrest W. Force analysis of individual muscles acting simultaneously on the shoulder during isometric abduction. J Biomechanics 1973; 6: 385-93.

- Downar J, Sauers E. Clinical measures of shoulder mobility in the professional baseball player. J Athl Train 2005; 40:23-9. [500KB pdf]

- Evangelista N. The Inner Game of Fencing: Excellence in Form, Technique, Strategy and Spirit. McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Ghafouri M, Feldman A. The timing of control signals underlying fast point-to-point arm movements. Exp Brain Res. 2001;137:411-23.

- Gonzalez R, Abraham L, Barr R, Buchanan T. Muscle activity in rapid multi-degree-of-freedom elbow movements: solutions from a musculoskeletal model. Biol Cybern. 1999;80:357-67.

- Gonzalez R, Hutchins E, Barr R, Abraham L. Development and evaluation of a musculoskeletal model of the elbow joint complex. J Biomech Eng. 1996;118:32-40.

- Hogfors C, Peterson B, Sigholm G, Herberts P. Biomechanical model of the human shoulder joint – II: The shoulder Rhythm. J Biomechanics 1991; 24: 699-709.

- Hogfors C, Karlsson D, Peterson B. Structure and internal consistency of a shoulder model. J Biomechanics 1995; 28:767-77.

- Hsu J. Handbook of French Baroque Viol Technique. A.R. Liss / Broude Bros., 1982.

- Ianotti J, Williams G, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Lippincott, 2006.

- Matsuo T, Fleisig G, Zheng N, Andrews J. Influence of Shoulder Abduction and Lateral Trunk Tilt on Peak Elbow Varus Torque for College Baseball Pitchers. J Appl. Biomechanics 2006; 22:93-102.

- Pitman B. Fencing: Techniques of Foil, Épeé and Sabre. Crowood, 1988.

- Pousson M, Amiridis I, Cometti G, Van Hoecke J. Velocity-specific training in elbow flexors. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;80:367-72.

- Rogers E. Fencing: Essential Skills. Crowood, 2003.

- Sabik M, Torry M, Lawton R, Hawkins R. Valgus torque in youth baseball pitchers: a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004; 13: 349-55.

- Schwamberger K. Exercises for Viola da Gamba. Rahter, 2001.

- Viggiani A. Lo Schermo. Venice, 1575.

- Visentin P, Shan G. The kinetic characteristics of the bow arm during violin performance: an examination of internal loads as a function of tempo. MPPA 2003; 18:91-9.

- Wrbaškic N, Dowling J. The relationship between strength, power and ballistic performance. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008; 18: (2007 Nov 20 epub).

- DSM. Unplugged Folias & Romanescas: Acoustics Très Tendrement, Finances Très Tendres. CMT blog, 12-MAY-2007.

P etites Règles qu’il faut observer dans les commencements.

- Ne lever jamais aucun doigt sans nécessité.

- Les Pieds sur le Plat.

- Le Pouce suis ainsi le doigt du milieu.

- Montrer le Poignet.

- Ne creuser point la main.

- Ne point faire le dos d'âne.

- Fermer le poignet en poussant, et ne présenter le dedans.

- Ouvrir le poignet en tirant.

- Commencer le Poussé par le bout de l’Archet.

- Commencer le Tiré tout proche le poignet.

- Soutenir la Pointe de l’Archet

- Tirer et pousser à Angles droits.

- Ne point tendre le coude.

- Ne point faire de Grimace.

- Ne point souffler.

[Little Rules for Beginners

- Never move any finger unnecessarily.

- Keep the feet on the floor.

- The thumb is the key.

- Show the wrist.

- Don’t ‘dig’ the hand.

- Don’t do the ‘donkey-back’ (sway-back posture; lordotic spine curvature).

- Close the wrist while pushing, and don’t present the inside.

- Open the wrist drawing from it.

- Begin the stroke by the tip of the bow.

- When you begin the pull, close the wrist.

- Support the point of the bow and pull and push at right angles.

- Don’t extend or stretch the elbow.

- Don’t grimace.

- Don’t blow.]”

Hi there! I'm a viola da gamba player since 2001, and started to work with Ruby Instruments in 2005. I'm currently studying functional physiology at the Clinique du Musicien et de la Performance Musicale in Paris, France. Thanks a lot for this article. I wonder if I can further contribute to the study of bowing biomechanics, as I'm extremely interested in it, and functional physiology as well (especially scapular/upper limb).

ReplyDeletePlease let me know if your article can be expanded by working with myself, as I'm always keeping a log of everything I do.

Just a thing: the scap load is very different when playing standing up like on a Ruby Gamba, which is the one I play the most. I find it hard to play without getting quickly tired (as the instrument is set on a tripod —unlike an acoustic gamba which is on my body—and I have to move around, so there are compensations in the feet and pelvis, and of course the whole lower limb tendino-muscular chain) at the scapular level and without having to flex knees a little to "unlock" them... Otherwise it's impossible to stay up for hours bowing on this instrument! It's an extremely rewarding one, but regarding potential pathologies including dystonia, it's one of the best ways to get some.

Regards,

JB Collinet

Tertis originally studied the violin in Leipzig and at the Royal Academy of Music in London. He became a violist when Alexander Mackenzie recommended him to become a viola player instead. viola teacher

ReplyDeleteWithin a survival situation it isn't always possible to have a survival kit at hand. Maintaining warmth is one of the key factors for survival and staying alive. how to make A BOW DRILL

ReplyDelete