I believe in as wide a range of musical involvements as is feasible given the Reality of Life.”

— Roger Reynolds, 1993

DSM: Cellist Rohan De Saram performed with violinist Mark Menzies and cellist Erika Duke-Kirkpatrick last month (16 March) at REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater at the Walt Disney Concert Hall) in Los Angeles —— Roger Reynolds’ ‘Focus a beam, emptied of thinking, outward... ’

CMT: And Reynolds’ ‘Angel of Death’ was performed a month ago as well (on 10 March) by the Columbia Sinfonietta at Miller Theatre, Broadway at 116th Street, in New York. These are fascinating pieces. But the taste for them is—What would you say?—an ‘acquired’ taste. They do get performed. But it’s hard to find the events, hard to find the opportunities to experience them. Currently on the faculty of University of California at San Diego. Roger Reynolds is now 72 years old but is still as ‘young’ as ever. Originally trained in Engineering Physics at the University of Michigan, he co-founded ‘ONCE Group’ with Robert Ashley. The ONCE Festivals in Ann Arbor in the early 1960s were renowned among avant-garde music events. And the ONCE Group included some of the most influential and imaginative composers of the day. Reynolds won a Pulitzer Prize in 1989 (for ‘Whispers Out of Time’ for string ensemble) and has accumulated many other honors over the course of his career. His works typically include text and electronic elements, plus theatrical and multimedia performance art. And he’s a pioneer in multi-channel spatial effects—dynamic antiphonal effects that change during the course of a composition and may have significant improvisational latitude for performers. Google around, and you find countless musicians and composers who cite ‘former student of Roger Reynolds’ on their curricula vitae. So, despite the acquiredness of the taste and the comparative scarcity of performances of Reynolds’ works, there’s tremendous ‘cachet’ associated with claiming some association with this Grand Not-Old Man of the electro-acoustic avant-garde.

DSM: He’s always been interested in antiphonal and aleatoric effects. Reynolds’ DVD of Watershed (MODE Records) was the first classical music DVD engineered and produced for surround-sound. Even up to today, MODE produces Roger Reynolds’ work, including his theater-piece ‘Justice’ and a collaboration with poet John Ashbery on a cycle of words and music, entitled ‘Last things, I think, to think about’.

T he issue of self awareness is one of the most problematic things that any artist, perhaps any individual, encounters in his or her life. I would imagine that if you asked me, do I know myself better now than I did then, the truth is probably ‘No.’ What has changed is that [laughing] I care less about whether the connection between what I am ... It is folly to imagine that you are in complete control of what is happening. People use different metaphors, and the most common one in my experience is how composers talk about the work ‘taking over’. Of course, that’s nonsense. The piece doesn’t take over. But what does happen is that your ability to move things or to alter assumptions diminishes as the amount of material that already establishes normatives grows. Exactly how this relates to the question of self awareness I’m not entirely clear.”

— Roger Reynolds, on the issue of a composer’s self-awareness, at National Institute of Arts and Letters, 1973.

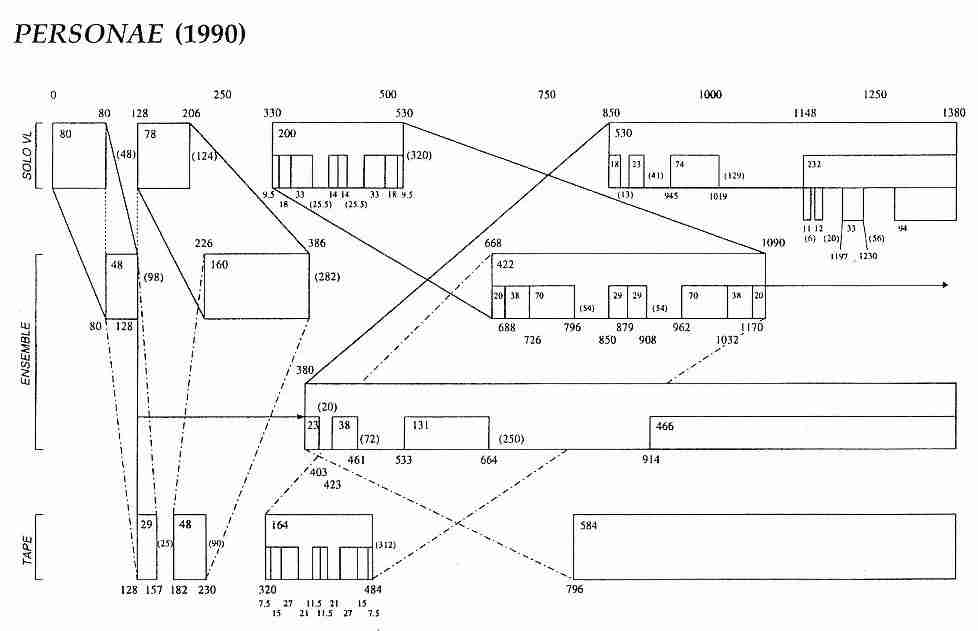

CMT: Reynolds has always ‘pushed the envelope’ rhythmically, too. Traditionally, western music has been dominated by binary structural elements: two-bar phrases, four-bar phrases, eight-bar, sixteen, and so on. That’s the normative pattern of the temporal structure of events and how they fit into larger units, assuming a coherent tempo. Of course, not all musical cultures deal with time in this way. But powers of base-2 are predominant. Regarding neurophysiology and cognition, Paul Fraisse’s book, The Psychology of Time, notes the importance of change—there must be change on a timescale that is neurobiologically congenial, for mammals to be able to perceive a stimulus. Constancy is ignored—it is part of how our nervous system automatically filters and reduces the sensory overload and makes it possible for us to attend to the things that matter most. In his compositions, Reynolds strives for novel aesthetic effects using hierarchical ‘self-similarity’ elements—to establish constancy where he wants it, and thereby to temporarily or progressively diminish the listener’s attentiveness to those voices that are exhibiting self-similarity or relative constancy. Each self-similar element may be echoed by subsequent statements in other voices, and those echoes in turn become transiently ‘new’ and attract a disproportionate amount of the listener’s attention for a time. The soloist plays, the ensemble plays, the synthesizer plays, and the soloist plays, but the relationship between solo and ensemble and synth starts shifting. In designing his unique polyphonal forms, Reynolds uses graphical compositional plans to manage the multiplicity of simultaneous layers of sound that he is composing.

DSM: One of Reynolds’ early works was ‘The Emperor of Ice Cream’, scored for three instrumentalists and eight singers. The score includes stage directions that show how, over time, the singers should redistribute themselves on-stage in order to alter the antiphonal ‘spatiality’ of their sounds. The entire process is depicted in his score and formal performance plan.

T his is a little difficult to see, but this is graph paper, and down here is a square, and down there is another square. That square represents the performance space, or it represents this room. What this represents - that curve, that curve, or this one - is a potential path that a sound can take. So let’s say that I say, ‘Abracadabra, abracadabra, abracadabra,’ that I say that continually, and that sound, ‘abracadabra,’ starts here and moves closer to you and then moves away. And what I’ve done is to design a variety of paths that aren’t just abstractly attractive, but that have actual, visceral effects on one. A fly-by is a very effective gesture in sound space. So I’ve become involved with the idea of using the spatial acuity of the human perceptual system as a component of my music. It involves, like everything else, a lot of planning and informed intuition.”

— Roger Reynolds

CMT: Roger’s fascination with explicitly scoring ‘processes’ leads me to wonder whether he’s ever used ProForma’s ProVision business-process modeling software to design one of his compositions. Or CaseWise or one of the other modeling languages. Just as the language standard for XML has been extended to MusicXML, is it not reasonable that BPML or BPEL might be extended to, say, MusicBPML or MusicBPEL to accommodate the music-specific syntactic and expressive requirements of music? Those BPM application packages include the possibility of Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation (MCMC) and Discrete-Event Simulation (DES)—things that would be interesting and valuable to composers like Roger, I would think. These object-oriented BPM apps would help not only with the exploratory phases of composition—to make the process of discovering what process-flow works best for the aesthetic effects you’re after—but also with the practical staging and production phases—to “vet” or validation-test the performance implications of what you’ve written before you go and try to rehearse it.

If you think about a traditional musical score, you realize that a violin part to a Mozart sonata does not tell the violinist which way to move the bow, where to put his finger on the strings, how to hold the violin, how hard to push, how fast to pull the bow. It doesn't tell him any of those things. It just says: I want this note here, and then this one and then this one, and this should be louder than that one, and so on. What I’m trying to see, with a technical score, is whether there are parallel ways of addressing technological issues which are perhaps much more variable even than such a phenomenon as the technique of an individual instrumentalist.”

— Roger Reynolds, 1993

DSM: UCSD’s $52 million New Music Center began contruction this January. Its 400-seat recital hall was designed by acoustical engineer Cyril Harris. Designed by LMN Architects of Seattle, the three-story, 47,000-square-foot design will have, among other things, configurable ‘black box’ theatre.

CMT: Yes. I visited the site earlier this winter, during a trip to UCSD. The flexibility that’s incorporated into the New Music Center’s design should be ideal for performance of multi-media works like Reynolds’ pieces. The UCSD New Music Center facility is due to open in early 2009.

- Roger Reynolds website

- Roger Reynolds page at Edition-Peters

- Roger Reynolds page at U.S. Library of Congress

- Roger Reynolds concerts at U.S. Library of Congress, Music Section

- Roger Reynolds, ‘Angel of Death’, 2005.

- Society of Composers

- Roger Reynolds page at UCSD

- Roger Reynolds Wathershed DVD clip (36MB mpeg)

- Roger Reynolds, The Emperor of Ice Cream clip (1MB mp3)

- Center for Research in Computing and the Arts (CRCA) at UCSD

- Chantal Buteau webpage at Brock Univ Dept of Maths

- International Computer Music Conference (ICMC2007), 27-31 August, Aalborg Universitet, Copenhagen

- Beran J, Mazzola G. Analyzing Musical Structure and Performance: A Statistical Approach. Statistical Science 1999;14(1):47-79.

- Berry W. Structural Functions in Music. Dover, 1987.

- Buteau C. Topological Motive Spaces and Mappings of Scores' Motivic Evolution Trees. Colloq Math Theory 2005;347:1-29. (1MB pdf)

- Bueteau C, Mazzola G. From Countour Similarity to Motivic Topologies. ETH Zurich, Working Paper, 2000. (1MB pdf)

- History of ONCE Group

- Clare E. Music, Mind and Structure. Routledge, 1989.

- Cook N, Everist M, eds. Rethinking Music. Oxford Univ, 1999.

- Cope D. Virtual Music: Computer Synthesis of Musical Style. MIT, 2001.

- Deutsch D. The Psychology of Music. Academic, 1998.

- Dodge C, Jerse T. Computer Music: Synthesis, Composition and Performance. Schirmer, 1997.

- Fraisse P. The Psychology of Time. Greenwood, 1976.

- Hanninen D. Orientations, Criteria, Segments: A General Theory of Segmentation for Music Analysis. Journal of Music Theory 2001;45(2): 345-433.

- Hasty C. Segmentation and Process in Post-tonal Music. Music Theory Spectrum 1981; 3(1): 54–73.

- Hasty C. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford Univ, 2003.

- Hoerl C, McCormack T, eds. Time and Memory: Issues in Philosophy and Psychology. Oxford Univ, 2001.

- Howell P, West R, Cross I, eds. Representing Musical Structure. Academic, 1991.

- Huron D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the PSychology of Expectation. MIT, 2006.

- Krebs H. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. Oxford Univ, 1999.

- Lerdahl F, Jackendoff R. Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT, 1996.

- Lewin D. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. Oxford Univ, 2007.

- London J. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford Univ, 2004.

- Mazzola G, Noll T, Lluis-Puebla E, eds. Perspectives in Mathematical and Computational Music Theory. epOs, 2004.

- Noll T, Garbers J. Harmonic Path Analysis in RUBATO.

- Ockelford A. Repetition in Music: Theoretical and Metatheoretical Perspectives. Ashgate Press, 2005.

- Piekut B. From No Common Practice: The New Common Practice and its Historical Antecedents. Was There Even an Actual Common Practice? American Music Center. NewMusicBox, 01-FEB-2004.

- Reynolds R. Form and Method: Composing Music. Routledge, 2007.

- Reynolds R. Process and Passion. (Pogus, 2004.)

- Reynolds R. ‘Composition and Process for Transfigured Wind’

- Reynolds R. Watershed DVD. (MODE Records, 1999.)

- Reynolds R. All Known All White. (Pogus, 2002.)

- Reynolds R. Whispers Out of Time; Transfigured Wind 2. (New World, 1992.)

- Roeder J. Pulse Streams and Problems of Grouping and Metrical Dissonance in Bartók's 'With Drums and Pipes' MTO 2001;7(1).

- Sharp A, McDermott P. Workflow Modeling: Tools for Process Improvement and Application Development. Artech, 2001.

- Smalley D. Spectro-morphology and structuring processes. In Emmerson S, ed, The Language of Electroacoustic Music, pages 61–93. MacMillan, 1986.

- Temperley D. The Cognition of Basic Musical Structures. MIT, 2004.

- Schrock R. Review of Paul Dresher Ensemble’s performance of Reynolds’ ‘Submerged Memories’, 10-APRIL-2006.

- ProForma Corp. website

- CaseWise Ltd. website

- BPMI website

- WfMC website

- SMDL, MML and related, CoverPages.org

- MusicXML.org website

- OpenMusic on CLOS platform, at IRCAM

- Csound project at SourceForge

No comments:

Post a Comment