DSM: I was invited to a Halloween party the other day, an intimate gathering of about 10 people, and the people hosting it asked if I could come up with a suitably spooky piece to play after dessert.

CMT: Brother. Surely you begged off.

DSM: Well, the couple have been friends of mine for more than 10 years. And they’re not obtuse people. In fact, the request was posed as a question, “What is the scariest, the most seriously disturbing piece of music you’ve ever played?” And off-hand, I couldn’t really say. I’d never thought about it. I tend to stay away from overtly programmatic pieces. And it seems to me that trying to pigeon-hole the meaning and mood of a given work is naïve (in the case where a piece is first-rate, and the attempted categorization over-simplifies it and does violence to the expressive scope of it). Or else the piece in question is in fact second-rate and really does admit of a simplistic (and therefore aesthetically inferior) interpretation. Uggh.

CMT: So—you can be suckered by a throw-down challenge, is that it? What did you do—wrack your brain trying to recall especially sinister and diabolical motifs?

DSM: No—too tedious. But the typology of horror is pretty broad—there are many sub-types in the genre. So I started thinking of creepy movies—genuinely scary movies I've seen over the years—and then I took inventory of the composers whose biographies strike me as sufficiently unhinged—deviant in a way that is undeniably fright-o-genic.

CMT: Liszt has always impressed me as having an Anthony Perkins-like Psycho Norman Bates-ish quality. If you were looking for a satanic schizoid personality—an abject psychopath—Liszt in full bloom would be hard to beat, don’t you think? Late in life, didn’t he buy himself a bishopric or arrange for himself to be ordained as an Abbé or something? A rich man with a maniacal piety about him—now that’s scary!

DSM: Liszt definitely made it on my list! In fact, I think the Sonata in B minor is one of the spookiest things ever written.

CMT: Well, Charles Rosen considers the Sonata in B minor scary for its odd mix of dramatic bombast and preacherly sentimentality. (Charles Rosen. The Romantic Generation. Harvard Univ, 1998.)

DSM: Claudio Arrau, interviewed by Joseph Horowitz, clearly thought that the B minor Sonata was constructed by Liszt as a piece of programmatic drama—as a rendering of the Faust legend. (Joseph Horowitz. Conversations with Arrau. Knopf, 1992.) Brendel has thought so, too. (Alfred Brendel. Music Sounded Out. Robson, 1990.)

CMT: Let’s look at the score. It begins with these ominous, muffled groans. There is this eerie hallucinatory motif, in the Phrygian mode, that inexorably slouches down and down and down. If you play it very legato, dispassionately, the effect can be something like a a zombie, insensate and unstoppable—or vegetal and corrupt, like a fungus.

A ritenuto in m3 may be done in a heavy-handed, hokey way. But for the occasion you're invited to, I think it’s better left understated—to evoke death; a sad poling of Charon’s boat.

CMT: Brother. Surely you begged off.

DSM: Well, the couple have been friends of mine for more than 10 years. And they’re not obtuse people. In fact, the request was posed as a question, “What is the scariest, the most seriously disturbing piece of music you’ve ever played?” And off-hand, I couldn’t really say. I’d never thought about it. I tend to stay away from overtly programmatic pieces. And it seems to me that trying to pigeon-hole the meaning and mood of a given work is naïve (in the case where a piece is first-rate, and the attempted categorization over-simplifies it and does violence to the expressive scope of it). Or else the piece in question is in fact second-rate and really does admit of a simplistic (and therefore aesthetically inferior) interpretation. Uggh.

CMT: So—you can be suckered by a throw-down challenge, is that it? What did you do—wrack your brain trying to recall especially sinister and diabolical motifs?

DSM: No—too tedious. But the typology of horror is pretty broad—there are many sub-types in the genre. So I started thinking of creepy movies—genuinely scary movies I've seen over the years—and then I took inventory of the composers whose biographies strike me as sufficiently unhinged—deviant in a way that is undeniably fright-o-genic.

CMT: Liszt has always impressed me as having an Anthony Perkins-like Psycho Norman Bates-ish quality. If you were looking for a satanic schizoid personality—an abject psychopath—Liszt in full bloom would be hard to beat, don’t you think? Late in life, didn’t he buy himself a bishopric or arrange for himself to be ordained as an Abbé or something? A rich man with a maniacal piety about him—now that’s scary!

DSM: Liszt definitely made it on my list! In fact, I think the Sonata in B minor is one of the spookiest things ever written.

CMT: Well, Charles Rosen considers the Sonata in B minor scary for its odd mix of dramatic bombast and preacherly sentimentality. (Charles Rosen. The Romantic Generation. Harvard Univ, 1998.)

DSM: Claudio Arrau, interviewed by Joseph Horowitz, clearly thought that the B minor Sonata was constructed by Liszt as a piece of programmatic drama—as a rendering of the Faust legend. (Joseph Horowitz. Conversations with Arrau. Knopf, 1992.) Brendel has thought so, too. (Alfred Brendel. Music Sounded Out. Robson, 1990.)

CMT: Let’s look at the score. It begins with these ominous, muffled groans. There is this eerie hallucinatory motif, in the Phrygian mode, that inexorably slouches down and down and down. If you play it very legato, dispassionately, the effect can be something like a a zombie, insensate and unstoppable—or vegetal and corrupt, like a fungus.

A ritenuto in m3 may be done in a heavy-handed, hokey way. But for the occasion you're invited to, I think it’s better left understated—to evoke death; a sad poling of Charon’s boat.

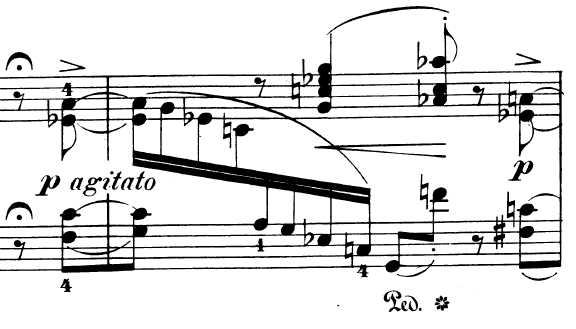

DSM: The exposition really takes the better part of the first 300 measures. There are the dead G’s in the first few bars, followed by dangerous and surprising leaping G’s (octaves) in m7-8. Then there is this cackling that begins in the LH in m15 and an agitato beginning in m18. We get the demented cackling again in m30-32, and the tonic B minor hits us with a vengeance.

CMT: You really need to keep a cool head to play this piece effectively. The arpeggi in m40-44 are so easy to rush. And the sense of urgency inhibits the player from reducing the sound enough by m44. If it is too loud you fail to evoke the whispering of fallen angels.

DSM: There is that hideous wailing in m18-22! The musical texture feels like a doomed Gustav Doré engraving. There are more deconstructions later on, notably in m113-119. Back and forth whispering and thundering, desperate pleading to be spared—from what we're not sure.

CMT: Trying to un-do the deal with the Devil, I imagine, if we believe that the Faust-Mephistopheles legend was behind some explicit program Liszt had in mind here when he composed the B minor Sonata. Then in m197 the agitato dissipates—like waking from a nightmare. Look too at m239 and beyond—the weird swirling effects. The key is a paradoxical D major, but, like a tight-shot in a movie, you know something bad is about to happen. The sunniness you wouldn’t trust as far as you could throw it!

DSM: Oh, and look at the reprise of the original theme, beginning in m277. What chaos! The house is haunted! The humans are on their own, completely without protection. The passage in m286-300 sounds like the Devil himself is there, complete with flames.

Then the recitative at m302: I like the mortified effect of putting the pedal down before the first note of the recitative begins.

CMT: Yes, but guard against playing too softly there, or the effect will be a cheap, fakey, stagey gasping "Goodbye, cruel world"—a bad movie. What you want the pedal to do is emulate the persisting pulse of a person who is in a coma. While it may be true that they may be mortally injured, they are unconscious. They don't participate in the scene as agents who have plans or intentions. Instead, their cognition is gone—they're inert and don't respond. The heart and noisy breathing, the brainstem and some low-level reflexes—elemental and tenacious—are the source of what you see and hear. To keep from being stagey at m302, you just need to remember that you’re in a coma.

CMT: The ghostly-cold C minor in m311 is another feature that convinces me that this Sonata is one of the scariest pieces ever. And in m415-433 we are apparitions, floating out in some black void.

Here are a few representative recordings to guide you, as you revise your decisions on how to handle this piece (or your scary excerpt from it) for your friends' party:

- Claudio Arrau. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Philips, 2002.)

- Clifford Curzon. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Polygram, 1997.)

- David Deveau. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Naxos, 1994.)

- Vladimir Feltsman. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Sony, 1989.)

- Annie Fischer. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Hungaroton, 1996.)

- Emil Gilels. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (RCA, 1993.)

- Vladimir Horowitz. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (EMI, 2005.)

- Jeno Jando. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Naxos, 1994.)

- Barbara Nissman. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Pierian, 2003.)

- Artur Pizarro. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Brilliant, 2001.)

- Mikhail Pletnev. (Deutsche Grammophon, 1998.)

- Sviatoslav Richter. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Polygram, 1998.)

- Russell Sherman. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Proarte, 1993.)

- André Watts. Liszt Sonata in B Minor. (Sony, 1996.)

And for a fine survey of the philosophy of horror, consistent with some of the musical ideas we’ve shared above, try Julia Kristeva’s excellent little book:

I take it you're going to go to the party dressed up as Liszt then?

No comments:

Post a Comment