W hen at last Justine arrives, he’s at the piano

the hammers strike and rise

with his fingers, and the pedal’s damp

shifting carries through the instrument

as waves echo through the frame of a ship...

Now he thinks perhaps the music’s

More like a map of rain hitting water—

He’s moving closer to her without moving;

And how wonderful to be held from her

at last by nothing but the song's duration—”

— Wayne Miller, ’What Night says to the Empty Boat’, p. 73.

I ’d first listened to Mara Gibson's new 16:30 work commissioned by Mark Lowry of newEar Contemporary Music Ensemble in July. The DVD has Mark performing vibraphone, log drum, woodblock, gong, tam-tam, songbird whistle, cymbal, and miscellaneous percussion, accompanied by video imagery and film by Caitlin Horsmon. Bob Beck rendered a high level of engineering and production values achieved in this recording.

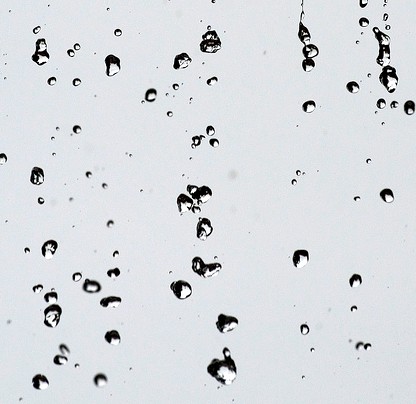

T he beauty of the chromatic intoning of vibraphone, punctuated by tolling woodblock, drum, and, less frequently, other instruments captured my interest from the first listening. The glisses and pitch-bent post-processed sounds of the vibraphone acoustically paralleled the imagery, the lateral motion of water in the foreground and in the distance; the water droplets in air, falling under gravity in parabolic arcs; the globules of water separating from a stream; the intercalating pastel cloud layers.

B ut now several months later—having just last week returned to the midwest after a period at our home on the East Coast, and having driven through some of the areas of hurricane-caused power outages and natural devastation—these textures and narrative arcs of ‘Map of Rain Hitting Water’ evoke different meanings for me. The watery surfaces now seem ominous and obscure what lies beneath.

T he reflections imply sky and sun, but these seem untrustworthy. The eddies and vortices imply structure and hidden currents, turbulence: the violence and indifference of Nature to humanity.

T he speed of the current makes abundantly clear how rapidly we will be swept away, annihilated, pointlessly. The accelerando/ritardando phrasing imparts a large-scale 2+ minute hypermeter to the piece.

N o animals or other sentient creatures are seen anywhere in Horsmon’s imagery here... bulk matter only, liquid and air. The abruptly changing frame-rate... declares a capriciousness of our frame of perception, together with Nature’s propensity to precipitous, emergent change, against which our human wishes and needs are respectively futile and irrelevant.

T here is midway through the film a montage of stop-action stills, with different transparency/saturation settings, calling into question what is motion. It brings to mind horror film sequences built up out of successions of freeze-frame stills.

T he very high-speed video of the water droplets, together with digitally-stretched contrast and/or edge-sharpening, gives heightened perception of the separateness of the individual [droplets].

W e have here a sort of ‘video-monitor-as-painter’s-canvas’ effect... a palimpsest of successive masks and over-writing of previous images and surfaces.

T he film draws our attention to the very thinness and 2-D nature of our existence in the biosphere, between the sky and the depths of water.

I n fact, most of the film is of deep water: the first 5:45 is sky; second 6:00 is water; third 4:45 is water hurled into sky—with gradual transitions between these segments.

T he piece conveys feelings of loneliness and alienation that arise from our understanding that we are alone in the universe and insignificant in its workings. Underneath the performer’s punctuated observations and soliloquy about fate and the stream of events that occupies our attention while we are alive is a certain forboding, a fear of nothingness.

T hat we are in some inescapable way alienated from Nature is an old concept, going back at least to Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th Century. It is also a notion that coheres with our current environmental problems, insofar as our estrangement from Nature involves a hubris that forecloses upon developing an awareness and regard for how we depend upon Nature, in such a way that we would stop harming Nature.

R elinquishing whatever agency I have in the presence of the bulk matter around me reveals my beholdenness to the agency of other humans who are living now and who will take care of me in my dying days and who will outlive me, and the susceptibility of my remains and the residue of my life’s work to the agency of all creatures and natural processes that persist beyond my tiny lifetime.

T he harsh contrast and unblinking lens of the camera—together with the continuous, unflinching sound of the music—announce the abject hopelessness of our achieving any anonymity in the flesh, or participating in any genuine reciprocity with Nature.

S uch existential worries are absent when reciprocal trans-corporeality involves the definitely spiritual, or “more than human”, or involves an ambiguity or reversibility afforded by the hardly-human-at-all, or as-minimally-human-as-possible, as in Wilderness or Zombieness.

O ne can make some sense then of this piece’s assertion that we might be estranged from the flesh without that meaning either that such estrangement puts us really outside the flesh, or that landscapes including sky and water are themselves not fleshy. We are estranged, every bit as much as sky and water are patently fleshy.

T his is a superb composition, an excellent film, a beautiful performance, an excellent recording—sufficient to propel an evening’s meditation and beyond.

- Mara Gibson website

- Caitlin Horsmon website

- Mark Lowry/newEar website

- Wayne Miller website

- Abram D. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. Vintage, 1997.

- Brown C, Toadvine T, eds. Eco-Phenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself. SUNY, 2003.

- Cataldi S, Hamrick W, eds. Merleau-Ponty and Environmental Philosophy: Dwelling on the Landscapes of Thought. SUNY, 2007.

- Cook D. Adorno on Nature. Acumen, 2011.

- Eder K. The Social Construction of Nature. Sage, 1996.

- Honneth A. Reification: A New Look at an Old Idea. Martin Jay, ed. Oxford Univ, 2008.

- Kristeva J. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia Univ, 1982.

- Merleau-Ponty M. The Visible and the Invisible, followed by Working Notes, ed. Claude Lefort, tr. Alphonso Lingis. Northwestern Univ, 1968.

- Miller W. Only the Senses Sleep. NewIssues, 2006.

- Toadvine T. Merleau-Ponty's Philosophy of Nature. Northwestern Univ, 2009.

- Vogel S. Against Nature: The Concept of Nature in Critical Theory. SUNY, 1996.

No comments:

Post a Comment