T he excellent performance last night by pianist Paul Lewis at the Mozart-Saal in the Konzerthaus in Vienna provided some new insights about acoustic effects that are idiomatic of piano that may have interested Schubert late in his composing career.

T he excellent performance last night by pianist Paul Lewis at the Mozart-Saal in the Konzerthaus in Vienna provided some new insights about acoustic effects that are idiomatic of piano that may have interested Schubert late in his composing career.T here are many passages in the Vier Impromptus (D 935, 1827), Fantasie (D 760, 1822), and Sechs Moments musicaux (D 780, 1823-28) that have emphases with the sustain pedal applied—the Sechs Moments more than the others. The impression we receive as the sound “blooms” or blossoms in the few hundreds of milliseconds after the chord’s strings have been struck and sympathetic resonances are established in other strings and in the soundboard amounts to a tactile/haptic sense of flow—of a “systolic” pushing of blood through large blood vessels, and of the blood vessels’ elasticity, acting as a “reservoir” with network-like capacitance to absorb the flow and to subsequently dissipate it in the rete of smaller vessels beyond.

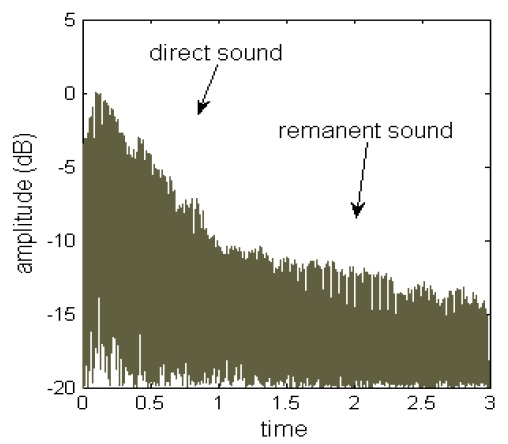

I t requires a piano with an efficient, high-impedance soundboard with a high Q-factor (fast decay of high overtones). You can play around with these properties with the Pianoteq software if you like. The software enables you to alter or exaggerate the “bloom”—how quickly or slowly it develops after the hammer strikes the strings; how long it takes for it to ring-down and decay while the sustain pedal is depressed.

I n Lewis’s playing, we see the physical origins of the sound—besides the properties of the instrument itself, there are elements of his performance practice that contribute to his technique and the sound that it affords. For example, he places the piano bench very high—so that the top of the bench is almost even with the underside of the keyboard… Last night, it was only 2 cm lower than the surface of the flange that mounts the pedal mechanism to the underside of the Steinway Model “D”. The thighs slope downward, and this puts Lewis’s legs in an angle of slight extension—about 140° between the femur and the tibia shaft centerlines. His elbow is high as well—also in a position of slight extension.

I n Lewis’s playing, we see the physical origins of the sound—besides the properties of the instrument itself, there are elements of his performance practice that contribute to his technique and the sound that it affords. For example, he places the piano bench very high—so that the top of the bench is almost even with the underside of the keyboard… Last night, it was only 2 cm lower than the surface of the flange that mounts the pedal mechanism to the underside of the Steinway Model “D”. The thighs slope downward, and this puts Lewis’s legs in an angle of slight extension—about 140° between the femur and the tibia shaft centerlines. His elbow is high as well—also in a position of slight extension.L ewis’s pedaling technique involves, then, considerable so-called “concentric” contraction by the rectus femoris muscle of the right leg, in addition to the flexion of the ankle. The dynamics of Lewis’s right leg motions contributed substantially to the “blooming,” systolic sonic effects of the accent-sustains in these Schubert pieces.

W hy does this interest me? Because these pieces are introspective and quite emotional, and I want to think about how they came to be so. These pieces were created late in Schubert’s short life, after the consequences of his syphilis had begun to be apparent, and after his treatments with mercury compounds (one of the few modalities of “treatment” for syphilis in the 19th Century) had also begun to exert their neurotoxic side-effects.

W hile it is possible for those of us who are not musicians—who are not composers—to be oblivious to the rhythms of our bodies, to the rhythms of our life and of our mortality, it is pretty implausible that a composer, or any elite-level musician performer—would not notice. And, having noticed such things—especially abnormal things, changed or changing things, potentially life-threatening things—like the pulsatility of one’s heart that is altering day by day as it has to work harder; or palpitations of a chronic or sub-chronic abnormal heart rhythm; or the progressive dilatation of an abdominal aortic aneurysm; or the worsening of stenosis of the aortic valve in the heart, or worsening incompetence of the mitral valve—having noticed them, it is, I think, impossible for a composer not to attend to them. Impossible for those physical, kinesthetic effects not to creep into one’s music; impossible not to become a bit preoccupied or obsessed with such persistent sensory stimuli in one’s writing.

L ewis’s lucid, passionate, pulsatile playing of these late Schubert works last night—evocative as it was of preoccupations with systole, and pressure-wave run-off, and hemodynamics equations, and windkessel compliance, and vessel elastance and storage, and ventricular-arterial coupling, and how severe aortitis changes these things—caused me think of this. Life is short: compose like hell, while we can; play like hell, while we can.

- Paul Lewis website

- Schubert D. Sechs Moments musicaux. D 780 score at IMSLP

- Cruz R, et al. Chronic syphilitic aortic aneurysm complicated with chronic aortic dissection. Am J Surg. 2010;200:E64-6.

- Ghazy T, et al. A monstrous aneurysm of the descending aorta as a sole manifestation of tertiary syphilis. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2411.

- Goebl W, et al. Touch and temporal behavior of grand piano actions. J Acoust Soc Am 2005;118:1154-65.

- Hetenyi G. The terminal illness of Franz Schubert and the treatment of syphilis in Vienna in the eighteen hundred and twenties. Bull Can Hist Med. 1986;3:51-64.

- Huang H, et al. In vitro identification of four-element windkessel models based on iterated unscented Kalman filter. IEEE Tr Biomed Eng. 2011;58:2672-80.

- Miller D, Maleszewski J. The pathology of large-vessel vasculitides. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29(1 Suppl 64):S92-8.

- Park H. The relationship between the acute changes of the systolic blood pressure and the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity. Kor J Int Med 2007;22:147-51

- Roberts W, et al. Full blown cardiovascular syphilis with aneurysm of the innominate artery. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1595-600.

- Vaideeswar P. Syphilitic aortitis: Rearing of the ugly head. Ind J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:624-7.

No comments:

Post a Comment