T he mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan looked to create some of the most complex mathematical patterns of all time. We are all looking [listening]. The question is who can see [hear].”

— Simon McBurney, Ensemble Complicite, ‘A Disappearing Number’, London, Barbican, 2007.

C ognitive phenomena do not always respect the ‘boundaries’ that are observed by textbooks and conferences in cognitive science. Consider the mirror neuron system—neurons in the premotor cortex that fire both when observing and performing an action. This discovery has challenged the assumed distinction between perception and action in the brain. While the human capacity to perceive opportunities for action (i.e., ‘affordances’; Gibson, 1979) has been extensively documented, it appears that even non-action-related judgments are in the ‘currency of action’... Cognitive phenomena do not always respect the boundaries that we draw between people either. Cognitive science has been concerned with the individual in isolation. But there have been striking insights into the brain’s sensitivity to social information and the way in which people think and act cooperatively [as exemplified in music].”S peed for speed’s sake—or overly complex rhythmic structures, or insincere utilization of mathematical calculations as a performance or compositional device—can justly be criticized as aesthetically weak or contrived. Authenticity is threatened by throw-down theory. Virtuosic technic can only be redeemed by genuine feeling. The person in the street needs ‘ghazals’, not maths.

— Kevin Shockley (Center for Cognition, Action and Perception, Univ Cincinnati), Daniel Richardson (Cognitive, Perceptual & Brain Sci, Univ College London), Rick Dale (Dept Psychology, Univ Memphis), Topics in Cognitive Science 2009; 1:305-19.

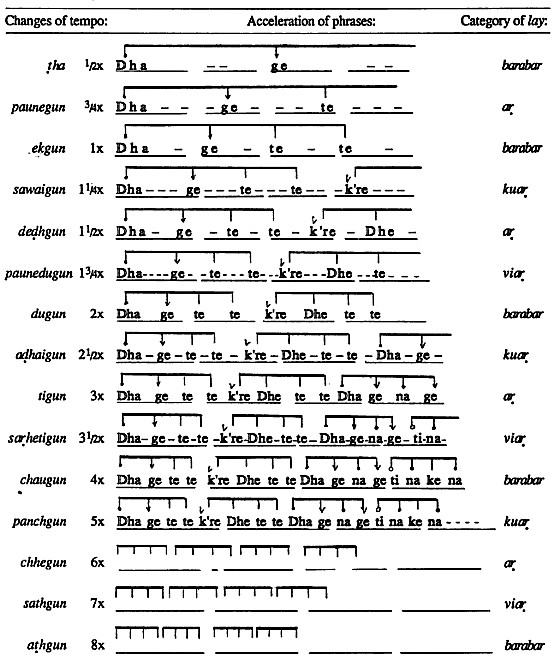

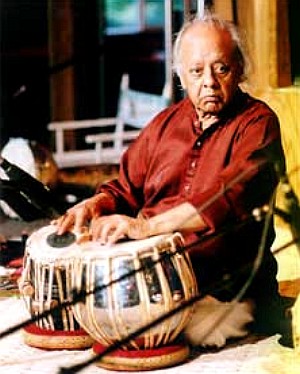

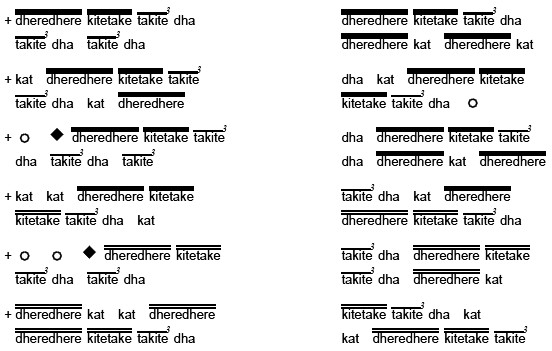

A nd yet... There are some musics whose rhythmic structure is unabashedly mathematical yet deeply moving. Tabla music, for example; and particularly performances by Ustad Zakir Hussain, or his father Ustad Alla Rakha who passed away in 2001. The mathematical design takes into account the length of each phrase, the duration of each pause that comes after the last DHA of each phrase, and the starting point of each tihai (see Gottlieb's book). There is a carefully worked-out, “composed” element, but there are necessarily the wonderful, small-scale human improvisational elements as well. [It's hard to conceive of anything less musical than a MIDI drum machine tabla executing mathematics-governed tabla rhythms. Gotta be “live”.] Here is link to a figure in Robert Gottlieb’s book on tabla, showing (left hand column) the rational-number relationships of tabla rhythms/metrical patterns.

[50-sec clip, Ustad Alla Rakha & Ustad Zakir Hussain, Together, ‘Taal Rupak’, 1.6MB MP3]

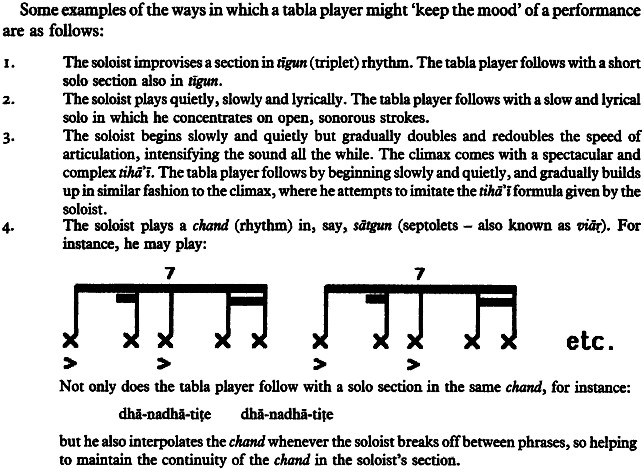

T he rhythmic pattern of this MP3 clip is a 'rupak taal', with 7 matras (beats). The word 'chhand' (metrical pattern) is used when constructing the linear superposition of one taal on another--'rupak chhand'.

T abla sets consist of a smaller teak or rosewood drum (dāyāñ=right=dominant_hand) and a larger metal drum (bāyāñ=left). Each has a drumhead (shāī or gāb) and is nested in cushions (chutta or guddi). The head is tuned with a small hammer (hathodi)—traditionally by inserting tuning blocks (ghatta) into the cords fastening the drumhead to the drum; alternatively, by wrench-adjustable threaded rods on modern instruments, much like other drums. The performer’s hands are coated with talc powder to provide the right ‘touch’ and to insure that the heads don’t get damaged by skin moisture or oils.

T here are several traditional styles of playing the tabla in India, each of which entails a specific playing idiom and performance rules. Two main styles of tabla are Dilli Baj and Purbi Baj. Dilli (or Delhi) baj developed in Delhi, and Purbi (meaning eastern) baj developed in the area east of Delhi. Delhi Baj is also known as Chati baj (chati is a part of the tabla from which a particularly sonorous tone can be evoked). Musicians then recognize six gharānās (schools or traditions) of tabla playing.

- Delhi gharānā

- Lucknow gharānā

- Ajrara gharānā

- Farukhabad gharānā

- Benares gharānā

- Punjab gharānā

E ach gharānā is distinct in terms of compositional and playing styles. For instance, some gharānās involve different positionings of the tabla and ‘bol’ percussive techniques. Today many of the distinctions between the gharānā have been blurred as successive generations of players have chosen to combine aspects from multiple gharānās to evolve their own ‘voice’. Some traditionalists say the era of authentic gharānā has basically ended insofar as the unique aspects of each gharānā have been substantially corrupted by individualistic mixing of styles and current socio-economic disincentives for sustaining the old “lineal purity” of gharānā through long and rigorous apprenticeships.

P unjab gharana music bears the influence of the Punjabi language and its mathematical, long-range order-admiring temperament. These are closely linked, and in fact a number of Hussain’s and Alla Rakha’s pieces incorporate densely rhythmic vocal parts as complements to the tabla and other instruments. Among the important composition forms of this style are Punjabi-Gat and Chakradar.

A jrada gharana features ‘kaidas’ (qā’idas, al Qaedas?). Graceful figures... less intricate canonical rhythmic structures, compared to Punjab pieces—at least in the examples I’ve been able to hear so far. As a special tonal characteristics of this tabla style are the phrases: GHE NA and GHE GE, GE NA DHA and DHA GE NE, and NE DHI and DHINE DHINA.

D elhi gharana is typically crisp and brilliant—more overtly individualistic compared to ‘collectivistic’, self-effacing tendencies in other gharana. The flowing, streamlike qualities of the rhythmic arc are distinctive. The Delhi-style is also known as Kinari-ka-baj-baj Kinar, which means, more or less, ‘Kinar under control’, while Kinar (literally: the edge, shore), a hard, clear sound is concerned, on the edge of the Dayan is generated. Characteristic phrases of this style are TI TE, DHINA GINA, DHAGE DHINA GINA, DHINA NOS.

M y own fascination with tabla music, its mathematical underpinnings, its drama arising from the tensions between individualism and collectivism, and its chamber-music-like intimations of psychophysical/neurocognitive ‘affordances’ between the performers—is just beginning. If you have experience in tabla performance or composition, I would be most grateful for your comments and suggestions as to how I might better understand and learn this beautiful music. Thank you!

P eople like us who believe in physics know that the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

— Albert Einstein.

- Hussain Z, Rakha A. Together. (OMI, 1990.)

- Hussain Z, et al. Best of Tabla. (MusicToday, 2007.)

- Ali Akbar College of Music

- Carnegie Hall Music of India / Weill Fellows Program, beginning 29-SEP-2009

- Burhoe Tabla Summer Retreat (Boulder, CO), 23-26-JUL-2009

- David Courtney website

- Tabla Taals at DrumDojo.com

- Tabla notation examples at Sapp.org

- Tabla lessons at Nirvana Music (Ocoee, FL)

- Ustad Alla Rakha page at AllMusic.com

- Naqqara-Tabla page at Wikipedia

- Courtney D. Learning the Tabla. Mel Bay, 2001.

- Gottlieb R. Solo Tabla Drumming of North India: Its Repertoire, Styles and Performance Practices. Motilal Banarsidass, 1998.

- Naimpalli S. Theory and Practice of Tabla. Popular Prakashan, 2008.

- Saxena S. The Art of Tabla Rhythm: Essentials, Tradition and Creativity. DK Printworld, 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment