I am a pianist and about six months ago I was diagnosed with Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD)—in both eyes. Actually, the two eyes are pretty different in how big the blind spot is. My right eye has a blurred area that makes music staves bend and notes blurry when I try to look directly at them. Dots disappear or blur into adjacent note-heads, 32nd beams look the same as 16th beams, and so on. The left eye is much worse, so what I see in the field that is affected relies almost entirely on what I’m seeing through my right eye. In spite of this, I can see almost well enough to read the page of music, so long as I am not looking directly at it—in other words, so the measures are off to the side of my ‘blind spot’. In the periphery, my vision is still pretty good. This adaptation—using my non-central visual fields for detailed seeing (I call them ‘non-central’; it seems wrong to call them ‘peripheral’, since it’s only a few degrees away from the central blind spot.) Also I find it works better for me to play on my MIDI keyboard with the chair raised higher, so I am looking down at the music instead of looking a bit upward, above eye-level, which is where the music is on my piano. It’s a far-from-ideal posture from a performance point of view. But looking downward at the music seems—for me, at least—to enable me to use parts of my field of vision that are less affected than other areas, which is a trade-off I’m happy to make.”Thank you, to the several people who emailed me about the CMT post about Pianoteq as a prosthetic ‘aid’, to enable people whose physical impairments would otherwise limit what they can do at the keyboard, to continue to perform on keyboard in the satisfying ‘manner to which they were accustomed’. Thank you, too, to the emailer above, for asking about visual impairments. There have been several other CMT readers who have had similar questions over the past several months, so now is as good a time as any to respond.

— Anonymous email to CMT.

Y ou should know that you are not alone in your search for solutions to your visual acuity problems and your efforts to continue playing. According to current U.S. statistics, about 7% of all pianists between age 40 and 100 have AMD. Pianists who have (had) AMD include:

- Arthur Rubinstein (1887-1982)

- Helen Kolozsvary (1922-2007)

- J. Wayne Streilein (1935–2004)

- Madeleine Titus (1914-2008)

- Earl Wild (1915-)

- Jennie Lois Windle (1915-)

- Sylvia Zaremba (1931-2005)

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment in the developed world. ‘Blindness’ as defined by the U.S. definition is a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse (20/200 in the better-seeing eye, where the acuity of left eye and right eye are substantially different). ‘Low vision’ is defined as a best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40 but better than 20/200 (in the better-seeing eye, if left and right are different).

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment in the developed world. ‘Blindness’ as defined by the U.S. definition is a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse (20/200 in the better-seeing eye, where the acuity of left eye and right eye are substantially different). ‘Low vision’ is defined as a best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40 but better than 20/200 (in the better-seeing eye, if left and right are different).AMD is the leading cause of blindness in Americans 50 and older, and its prevalence in the U.S. is expected to increase to 18 million by 2020. There are similar epidemiologic statistics in Europe and elsewhere.

M acular degeneration is a disease of the eye causing the light-sensing cells of the macula to malfunction resulting in partial or complete blindness. The macula is the central portion of the retina directly opposite the lens. The retina is the portion of the eye responsible for receiving light and sending electrical impulses to the brain that precipitates with sight. Specifically, the macula is responsible for the sharp, straight-ahead vision used in seeing fine detail, reading printed material, driving, watching television, reading things at normal magnification on computer screens, and recognizing faces.

M acular degeneration is a disease of the eye causing the light-sensing cells of the macula to malfunction resulting in partial or complete blindness. The macula is the central portion of the retina directly opposite the lens. The retina is the portion of the eye responsible for receiving light and sending electrical impulses to the brain that precipitates with sight. Specifically, the macula is responsible for the sharp, straight-ahead vision used in seeing fine detail, reading printed material, driving, watching television, reading things at normal magnification on computer screens, and recognizing faces. Loss of vision with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) normally occurs gradually and will usually affect both eyes, although not necessarily at the same rate or to the same extent in each eye. Macular degeneration is most often found in people over 60 years of age, although there are some hereditary forms of macular degeneration that affect children.

- Gradual decline of central vision which tends to progress at different rates in the two eyes

- Difficulty reading or performing tasks that require the ability to see detail

- Straight lines appear distorted

- Center of vision appears distorted compared to the rest of the scene.

- A dark, blurry area or "white out" appears in the center of vision

- Color perception changes or diminishes.

- Do any of the lines look wavy, blurred or distorted? (All lines should be straight, all intersections should form right angles and all the squares should be the same size.)

- Are there any "missing" areas where you can't see the grid lines?

- Are there any "dim" areas in the grid?

- Are you unable see all corners and sides of the grid when you are focusing on the dot in the center?

If you answered ‘Yes’ to any of the four questions above for either eye, make an appointment with your eye doctor right away. You can print the page, mark the areas of the chart/grid that you’re not seeing properly, and bring your marked-up grid with you to your eye exam.

If you’ve recently been diagnosed with AMD, there are many good books and online resources that you and your family members can take advantage of. Some of them are in the list at the bottom of this post. Laser treatments and other standard therapy alternatives are covered in those resources, and I won’t go into those here. But there are some newer things that I’ll at least mention, with some links at the bottom to enable you to explore on your own.

Over the past several years, people who have severe AMD have received off-label treatment with Avastin™ (bevacizumab), an anti-VEGF drug made by Genentech that was the first anti-angiogenic therapy approved for treating colorectal cancer. Ophthalmologists reasoned that if Avastin could block blood vessel growth in tumors, it might also affect angiogenesis in “wet” AMD. Genentech’s Lucentis™ (ranibizumab) was recently FDA-approved specifically for the treatment of “wet” AMD, and it is similar in molecular structure and action to Avastin. In a large, two-year study, this drug stopped vision loss in more than 90 percent of patients studied and restored vision in 33 percent. Scientists are now comparing the efficacy of Lucentis and Avastin, since Avastin is much less expensive than Lucentis.

The recently introduced anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) intravitreal injections of Genentech’s ranibizumab (Lucentis™) and bevacizumab (Avastin™) generated a heated research argument: on the one hand Lucentis was proven effective and relatively safe in large prospective double-blinded studies, albeit this drug is expensive and might cost up to $1,000 per injection into the eye. Eyetech Inc’s pegaptinib (Macugen™) has the same anti-VEGF mechanism of action and is also quite expensive. On the other hand, Avastin is widely used worldwide as a low cost alternative for Lucentis, with an estimated cost of about $120 per injection, although its effectiveness and side effects were previously investigated only in smaller retrospective studies and only recently have been studied in larger prospective ones.

But those medications are used mostly in AMD that is already severe/advanced. They generally are not (currently) used in a pre-emptive or preventive fashion, or in early or mild cases of AMD. This may be in the process of changing, insofar as these medications—in clinical trials and in off-label observational studies—are evidently able to stop the progression of the disease, for two years or longer. How much longer is not known, since the clinical trials have not followed the patients for much longer than that yet.

L ooking to the right slightly seems to be better than putting the music in the center or putting it where I have to look a little off toward the left. I can’t imagine why this is, except maybe it has something to do with what parts of each eye are damaged by the AMD. My adjustments almost make it possible to play pieces that are very familiar to me. But I don’t know how much longer this trick will be adequate. I can imagine a couple of years from now the AMD might be worse and these little tricks won’t be enough anymore, and I’ll have to stop playing. Even now, it’s next to impossible for me to get a new piece and try to learn it. My sketchy non-central vision is good enough to remind me of what my fingers and mind already learned years ago, but it’s not good enough to enable me to learn an entirely new piece. But it seems to me that if I could just magnify things a bit—like I do on my PC when I’m reading an Acrobat document or something—then I would be able to manage. Increasing the size of the music would enable me to make-do with what I’ve got and the non-central vision would be enough if only the music were way bigger. Increasing the wattage of the music lamp doesn’t seem to help; just makes the glare worse. Does this make sense? Is there something different I should by trying? I saw the things you wrote about ‘assistive’ uses of Pianoteq for pianists with disabilities, and I thought you might have suggestions about pianists with AMD.”Interestingly and in regard to the remark in the email above about ‘non-central’ visual fields mitigating the deficits in the foveal/central field, earlier this year Lingnau and colleagues at the Technical University of Braunschweig studied training people to use a parafoveal retinal location for reading. The study was designed to find out which part of the visual field is best suited to take over functions of the fovea during early stages of macular degeneration. A region to the right of the area you are needing to read leads to best (most accurate; quickest) reading performance and the most natural gaze behavior (so that the eyes do not get tired right away).

— Anonymous email to CMT (continued).

By contrast, reading performance was severely impaired when Lingnau and the other researchers asked the subjects to use a region to the left or below the area of visual fixation. An analysis of the underlying eye-muscle behavior revealed that ‘practice effects’ were accompanied by a larger number of ‘saccade’ eye movements in the text direction and decreased the visual fixation durations. Their journal article explained the observed performance differences at different retinal locations in terms of the neurophysiology of the interplay of attention and eye movements. The research has important implications for the development of training methods for AMD patients who aim to retain the ability to read detailed material such as sheetmusic. Most specifically, the research suggests that it is beneficial for AMD patients to use a region to the right of their central blind-spot, much as the CMT emailer has independently discovered.

W hat other non-medical, non-pharmacological things can a musician with AMD do, to compensate for the visual deficit?

- Increase the contrast between light and dark objects;

- Reduce glare with proper lighting (halogen bulbs are better than low-energy fluorescent, which in turn are better than incandescent);

- Use curtains or shades to reduce ambient glare from light-sources near your piano;

- Play for short periods, taking breaks that do not involve other visually-intense activity before returning to the keyboard;

- Follow the nutrition (with vitamin supplements recommended in books and professional society / AMD support group websites; see links below) and lifestyle recommendations of ophthalmologists and other experts;

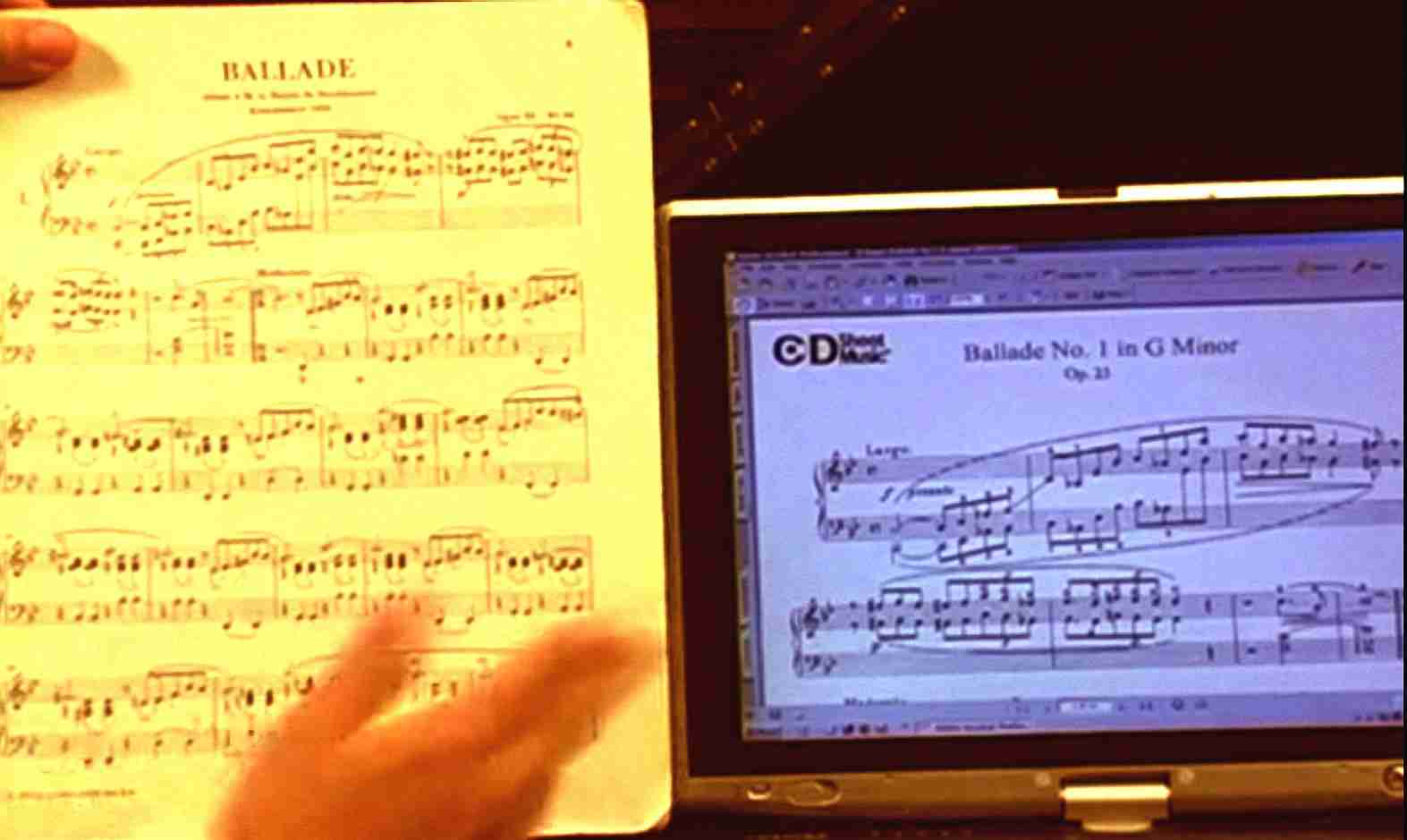

- Replace your music with nice, high-contrast magnified sheet music—either photocopy and enlarge it yourself, or use a PC-based means to display digital sheet music (usually as Acrobat pdf files, either purchased or obtained free online or scanned using an inexpensive scanner-printer-fax attached to your PC).

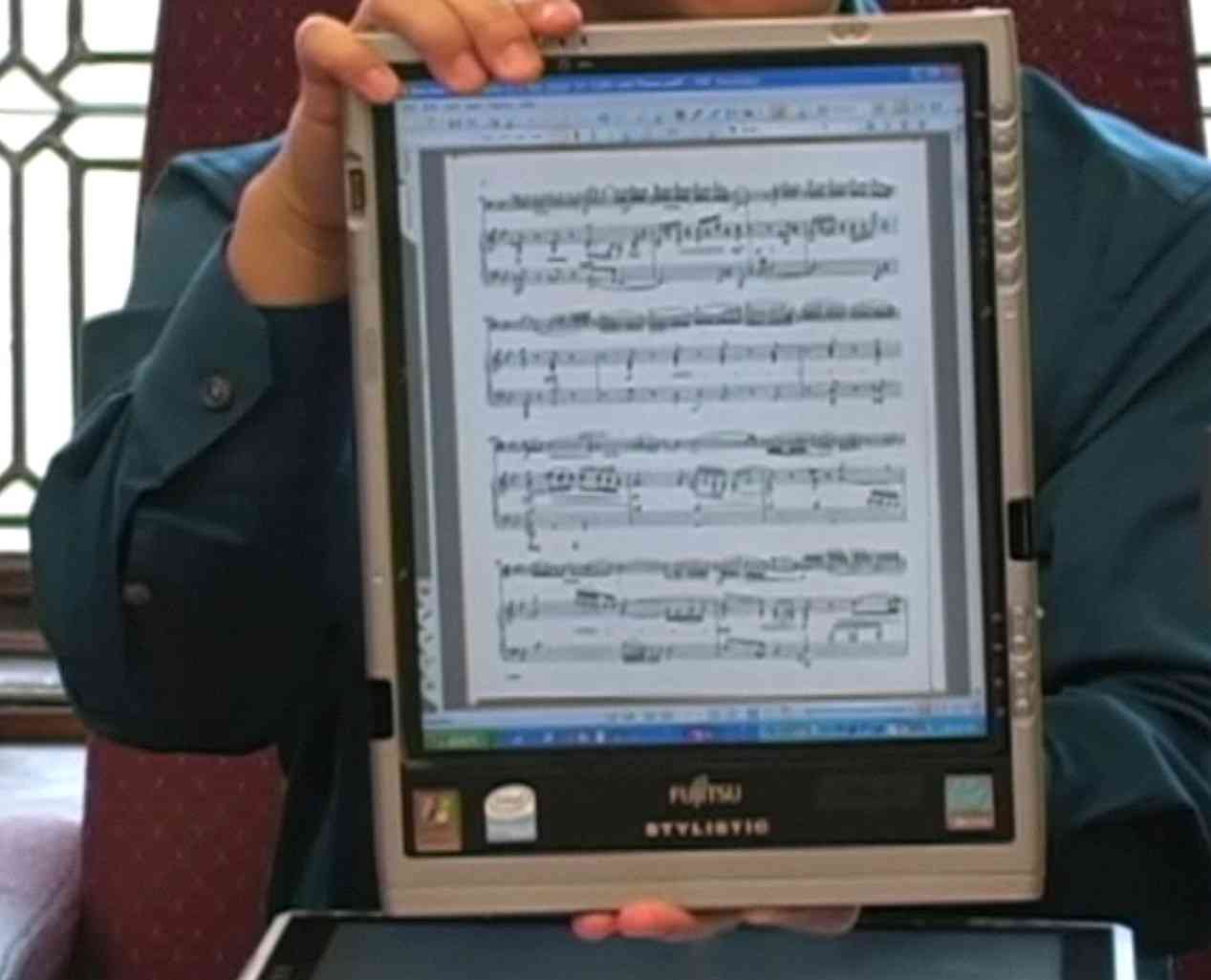

The thing that I like best about playing from digitized music on a tablet PC (or, for a bit more money, the MuseBook) is that you can set and adjust the magnification exactly how best suits you and the particular score you are reading. You can adjust the display contrast to be extra bright and contrasty if you want. You can tweak the RGB color controls on the monitor, to compensate for any color issues that your AMD is causing. You can’t do any of those things with hardcopy paper music.

By far the most extensive source of information on tablet PC-based music and practical technology and techniques to use it is on pianist Hugh Sung’s website and blog. His site has many practical tips and video demonstrations that explain how to do various things.

Please also consider getting an electronic pedal page-turning device for your PC. The AirTurn™ device is one that I recently bought. I find that it is very well built—sturdier than other options that are available. I like the Boss FS-6 dual pedal version of AirTurn™ a lot. The FS-6 pedal has a nice ‘feel’ and the pedals are spaced at a distance that makes it convenient to click pages forward and backward without risking a mistake and advancing too far. Other pedals that I have tried over the past ten years are either too dainty or too industrial/stiff and take your concentration away from your playing; this FS-6 pedal is non-intrusive and easy to get used to. Here is a photo of Hugh Sung at Curtis Institute, holding one of the Boss FS-6 pedals...

The AirTurn™ AT-104 is an RF device, so there are no wires snaking up from the pedal up to the piano. Attached to the pedal you have a little battery-powered transceiver that sits on the floor. (Mostly, its power consumption from the battery occurs when the device is transmitting pedal events to the PC, so the battery lasts quite a long time, even with active pedaling and prolonged use.) And the other part of the transceiver ‘pair’ is a tiny dongle that plugs into a USB port on your computer, much like dongle you use with an RF mouse. It receives the signals from its mate on the floor, enabling the software in your PC to scroll or jump down the page or page-forward or -backward. The AirTurn™ system has 65,000 RF pairing IDs available; you select an unused ID so the AirTurn™ will not interfere with your RF wireless mouse or other 2.4GHz RF computer accessories you have.

The ability to mark-up and save annotated copies of your sheet music—save them as different filenames so your original music remains ‘clean’—is a great advantage. And you can keep changing your annotations—no erasing! Very nice.

I am using my AirTurn™ with MusicReader™ software with my 1920x1200 and 1680x1050 monitors oriented in ‘landscape’ mode, and that works fine with my big “piano reading glasses” and even my bifocals. But MusicReader can be used with iRotate™ or other software to rotate the display to a vertical ‘portrait’ format instead of the default ‘landscape’ horizontal format.

I’m hoping at some point to try a dual-display monitor. Those are extensively used in financial trading—including people who do day-trading of stocks and commodities (or options and futures) at home—and by some gamers. The prices of dual-display monitors and the associated screen-splitting software have come down quite a lot over the past several years, due to their popularity. For music reading with diabetic retinopathy or other conditions that do not primarily involve a central macular deficit, maybe dual portrait-oriented displays—like the Zenview DuoPortrait 20 Pro pictured below—would be an advantage. But for other CMT readers—and maybe especially ones with early- to intermediate AMD where you are relying on ‘non-central’ visual fields—two landscape-oriented monitors may be better. In either instance, you will probably have to work out a different type of ‘stand’ for the monitors, because the ones that come with them from the factory (a) will not sit nicely on your Steinway and (b) will vertically position the centers of the monitors too high in your visual field. You will need either to go without a stand (monitors sitting on the piano in their bezel but without a stand) or find something that is squattier than the desktop-style stand that these products come with.

I’m hoping at some point to try a dual-display monitor. Those are extensively used in financial trading—including people who do day-trading of stocks and commodities (or options and futures) at home—and by some gamers. The prices of dual-display monitors and the associated screen-splitting software have come down quite a lot over the past several years, due to their popularity. For music reading with diabetic retinopathy or other conditions that do not primarily involve a central macular deficit, maybe dual portrait-oriented displays—like the Zenview DuoPortrait 20 Pro pictured below—would be an advantage. But for other CMT readers—and maybe especially ones with early- to intermediate AMD where you are relying on ‘non-central’ visual fields—two landscape-oriented monitors may be better. In either instance, you will probably have to work out a different type of ‘stand’ for the monitors, because the ones that come with them from the factory (a) will not sit nicely on your Steinway and (b) will vertically position the centers of the monitors too high in your visual field. You will need either to go without a stand (monitors sitting on the piano in their bezel but without a stand) or find something that is squattier than the desktop-style stand that these products come with.

Note that the digitized sheetmusic is moved forward or backward by each pedal press; it doesn’t ‘jump’ across many pages to follow D.C. or al segno or other ‘marks’. In such cases you may want to make your own pdf (using a ‘full’ Acrobat license, not just AcrobatReader) that replicates each section that is to be repeated, and assemble the replica page/pages sequentially, so that instead of doing multiple pedal presses to jump backward you are doing a single pedal press to go forward into the repeat, or a single pedal press to skip forward over a section to the segno.

These products are not just for musicians with visual impairments. I do think that AirTurn™ and related products will significantly help older pianists who have ‘essential tremor’ or arthritis or other conditions that make reaching and turning music pages difficult. To quickly and easily and reliably navigate your digitized music by pressing pedal footswitches is a joy, compared to struggling and often failing to turn the paper pages accurately and with confidence.

One last thing. I put together a little spreadsheet that shows the AREDS scoring method that ophthalmologists use to assess the severity of your AMD and estimate prognosis for disease progression on a 5-year timescale. If you wish, you can click on the screenshot below and download the Excel file and play with it. Discuss with your ophthalmologist the specific findings and changes that she/he observes in your eyes and ask about what changes you might expect over the next 5 years based on the AREDS studies. Overly-quick office exams are not what you want. You want to go to the eye doctor prepared with questions to ask, so you can get specific answers and good prognostic advice.

Please have a look at the links below. Email me with comments, questions, or suggestions you may have. If there is enough interest, I will compile them into future CMT posts on ‘assistive technologies’ for musicians. Thank you!

- Hugh Sung website

- AirTurn Inc. website

- Resources page at AirTurn Inc. (tablet laptops, scanners, music reading software, suppliers of sheet music)

- Hugh Sung page at Curtis Institute of Music

- National Eye Institute (U.S. NIH)

- NEI statistical data, prevalence of blindness by age-group

- AMD.org

- Foundation Fighting Blindness

- Macular Degeneration Support

- Macular Disease Society

- American Foundation for the Blind

- AHAF.org

- Schepens Eye Research Institute (Harvard Univ)

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group (AREDS). A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123: 1570-4.

- Ip M, Scott I, Brown G, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor pharmacotherapy for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol 2008; 115:1837-46.

- Jonas J, Ihloff A, Harder B, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab versus triamcinolone acetonide for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthal Res 2008; 41:21-7.

- Jun J, Kim Y, Kim KResolution of severe macular edema in adult coats' disease with intravitreal triamcinolone and bevacizumab injection. Kor J Ophth 2008; 22:190-3.

- Kadrmas E, Dyer J, Bartley G. Visual problems of the aging musician. Surv Ophthalmol 1996 40:338-41.

- Kook D, Wolf A, Kreutzer T, et al. Long-term effect of intravitreal bevacizumab in patients with chronic diffuse diabetic macular edema. Retina 2008; 28: 1053-60.

- Krebs I, Lie S, Stolba U, Zeiler F, Felke S, Binder S. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab therapy for early and advanced neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol 2008 Oct.

- Lim J, ed. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2e. Informa, 2007.

- Lingnau Q, Schwarzbach J, Vorberg D. Adaptive strategies for reading with a forced retinal location. J Vis 2008; 8: 6.1-18

- Lyons K, Pahwa R, eds. Handbook of Essential Tremor and Other Tremor Disorders. Informa, 2005.

- Mayo Clinic. On Vision and Eye Health: Practical Answers on Glaucoma, Cataracts, Macular Degeneration & Other Conditions. Mayo, 2002.

- Merciera E. Non-Age Related Macular Degeneration. Nova, 2008.

- Mogk L, Mogk M. Macular Degeneration: The Complete Guide to Saving and Maximizing Your Sight. 2e. Ballantine, 2003.

- Paul E. Conquering Macular Degeneration: The Latest Breakthroughs and Treatments. Trafford, 2006.

- Plumb M, Bain P. Essential Tremor. Oxford Univ, 2006.

- Roberts D. The First Year: Age-Related Macular Degeneration: An Essential Guide for the Newly Diagnosed. Da Capo, 2006.

- Samuel M. Macular Degeneration: A Complete Guide for Patients and Their Families. Basic Health, 2008.

- Schouten J, la Heij E, Webers C, Lundqvist I, Hendrikse F. A systematic review on the effect of bevacizumab in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophth 2009; 247:1-11.

- MusicReader B.V. website (The Netherlands)

- iRotate software

- PDFannotator software

- Zenview Duoportrait 20 Pro (total diagonal size: 34.4 inch (32.2 inch W x 12.1 inch H); total screen resolution: 2400 x 1600 pixels; Pixel pitch: 0.26mm; aspect ratio: 4:3x2)

- Zenview Manager multi-screen software

- NVIDIA GeForce graphics cards supporting dual monitors with display resolutions up to 2560 x 1600 pixels at up to 85 Hz

- NVIDIA nView multi-display software

- MagniSight.com

- SmartView (Humanware)

- IRTI digital magnifiers

- ClearView (Optelec)

- Merlin (Visiontech)

- Lucentis.com

- Avastin.com

- Macugen.com

- VisiVite (vitamin A 25KU, vitamin E 400 U, vitamin C 500 mg, Zinc 80 mg)

- DSM. Better Eyeglasses for Chamber Musicians? CMT blog, 16-NOV-2007.

- DSM. Assistive Technologies 2: ‘Disability Arts’ and Special User Interfaces. CMT blog, 28-MAY-2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment