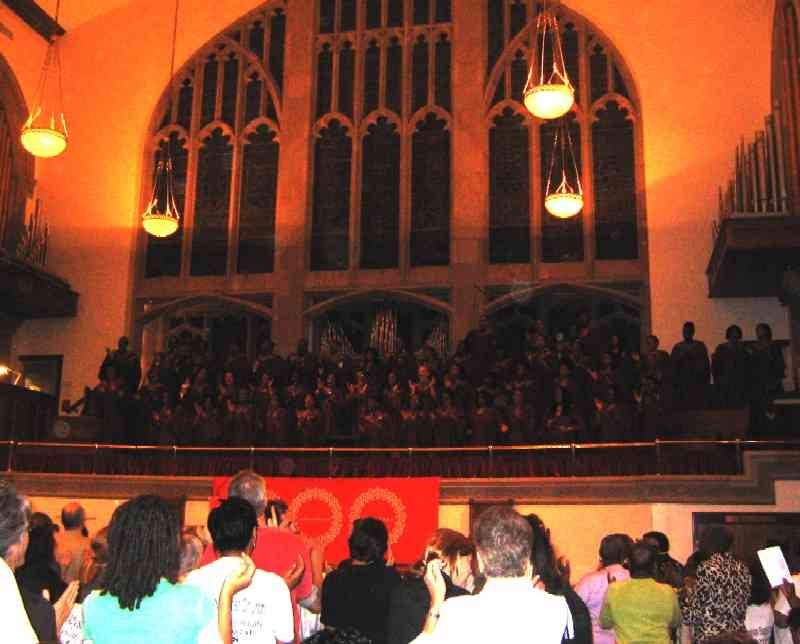

M usic has a unique ability to animate us, to initiate activity for people who are stuck for one reason or another. And it has a unique ability to help us to feel community with others, to bind us together and to reveal and restore bonds that were broken. These are true for all people. But they are true also for people who have diseases, whose bodies prevent them from starting on their own. Stutterers who cannot speak can, amazingly, sing perfectly. People with viral encephalitis lethargica, about whom I wrote in my book ‘Awakenings’, are helped greatly by music. The power of drugs to help—this waxes and wanes. But the power of music never diminishes. With Parkinson’s, the music must only have a beat, a clear-cut rhythm, to get the person un-stuck. With Alzheimer’s, the music must also be familiar music, music from a time in the person’s life before the dementia. Even with advanced dementia, when powers of memory and language are lost, people will respond to music. With a song, it is possible to discover that words are still in there. Finding that out can be very reassuring, say, to a person who has been unable, for 2 years or more, to call forth words to speak. Then, once we know that the words are still there, it is our task to see whether we can elicit them at other times [when music is not there] and make them available for general use [once again]. It is the basal ganglia, the brainstem, the cerebellum, and some parts of the motor cortex; it is the mammalian old hindbrain. That is where these music-related connections are, and why the ability for music to liberate a person is impervious to diseases that destroy other parts of the brain, the intellect. Actually, I say ‘mammalian’, but every time I do someone tells me about ... cockatoos. Perhaps it is not just mammals...”There is a tendency to place too much emphasis on thought—on higher brain functions and deliberation and intellect—when we think of how we understand and respond to music. To counterbalance that tendency, neurologist-author Oliver Sacks spoke yesterday at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York, in one of the events that comprise the World Science Festival. The two-hour program featured a performance of many selections of gospel music by the church's 53-member Abyssinian Baptist Choir. There was a standing-room-only sold-out crowd of more than 1,000 in attendance for the event. The World Science Festival was conceived by Columbia University physicist Brian Greene and his wife, Tracy Day, who is a broadcast journalist.

— Oliver Sacks, Abyssinian Baptist Church, New York, 31-MAY-2008.

- Over My Head (Arr., R. Jennings)

- Woke Up This Morning (Arr., J. Bolding)

- We’ve Come This Far by Faith (Arr., J. Bolding)

- Lift Every Voice and Sing (Arr., R. Carter)

- Order My Steps (G. Burleigh)

- Total Praise (R. Smallwood)

- That’s How the Lord Works (Arr., J. Bolding)

- Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel! (Arr., J. Bolding)

- For Every Mountain (Arr., J. Bolding)

- This Little Light of Mine (African American Spiritual)

Two CMT posts last month concerned assistive technogies, to help disabled people regain and maintain abilities to perform music, particularly in a chamber music setting. But the Abyssinian Baptist Choir concert last night and Dr. Oliver Sacks’s and Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts’s talks (and this CMT post) are reminders that music itself is an assistive technology that promotes the health of the individual and the well-being of the community/society.

Consider, too, that a dimension of the ‘intimacy’ that is definitional of chamber music idioms is that chamber music is assistive in connecting each of us with our true selves—it induces an intimacy of self-awareness, self-discovery, self-actualization. In other words, the intimacy of chamber music is not purely discursive, interpersonal intimacy. It is intra-personal as well; it is about intimate identity. Those who, through the ravages of Alzheimer’s or stroke or other conditions, have lost their memory of their own personal history or identity know this more acutely than the rest of us. The amount of the processing of musical stimuli (and the amount of the synaptic storage and processing associated with personhood and identity) that is located in lateral prefrontal regions, in motor cortex, and in the amygdala, hippocampus, and other limbic structures (ones that are only tangentially connected with intellect or volition) in the brain is suprising, as Grahn and others have recently observed in their fMRI imaging studies. The heart of the emotional brain responds innately to psychophysiological stimuli associated with realistic musical scenes and animalistic rhythms—even the mere suggestion of rhythms or songs, as Sacks says. Our true selves are (partly; substantially) down in those non-intellectual structures, too.

Those who, through Parkinson’s or other diseases, have lost their ability to initiate actions that manifest their will and their personhood also know that music can assist or restore these—a major point of Oliver Sacks’s remarks. There is a physiologic immanence that is fundamental to music—the rhythm of music is the vehicle for it, more than melody or harmony. The latter are ‘added bonuses’, as Sacks put it. Gospel singing is, apart from its other notable features, inherently physical, intensely rhythmic, radically anticipative, contagious.

The ‘intimacy’ of gospel singing as a species of chamber music is also inherently communitarian—the solidarity and support and intimate belonging and acoustically-mediated enclosedness of the congregation; the musical rhythm-enforced inclusiveness that accepts divergence and difference ( ‘alterity’ ). At one point during last night’s performance, one of the women Abyssinian Baptist Church congregants leapt into the aisle and began shaking and shouting ecstatically. Two of the ushers stood by, but the woman did not collapse. So moved by the music, she continued her rhythmic ‘speaking-in-tongues’ shouting and shaking, at a decibel level often exceeding that of the large choir. The chamber culture and the chamber singers welcome this and recognize and assimilate it as part of the intimacy of worship in community. Sacks recommended that musical training in the schools should be a major curriculum priority, given the large social and health benefits that are known to be associated with engagement with music. In enthusiastic agreement with this remark, the crowd cheered and gave Sacks a standing ovation.

S teven Mithen has written about this … his experience of discovering his own musicality. He was humiliated when attempting to sing as a child, and stayed away from singing for more than 30 years. Now in his forties, he decided he would take singing lessons for one year. Before he began, he got an fMRI scan of his brain. And, after singing for a year, he arranged to get another fMRI. The corpus callosum and other parts of his brain had dramatically changed in size. The changes were obvious. And it has been found in other musicians, too. We could look at fMRI scans of Albert Einstein’s brain or Brian Greene’s brain, and you could not tell the difference between the brains of mathematical physicists or cosmologists and the brains of ordinary people. But I dare say if you got an fMRI of any of the people behind me [gestures toward Abyssinian Choir members in loft] and you would say ‘This must be the brain of a musician’. It is that dramatic. Of course, it is not yet clear how much of this difference is due to genetics—music-induced structural differences in those who have already musical potential—and how much is from the musical training. But the effect is real. Engaging in music changes your brain.”The World Science Festival programs continue today with a performance by jazz singer Marilyn Maye (born in Wichita in 1930) at the Kimmel Center, with lectures by Robert Butler, David Sinclair, and Richard Weindruch entitled ‘90 Is the New 50: The Science of Longevity’ at the Eisner & Lubin Auditorium at NYU—how music may help us to live longer, in addition to helping keep our wits and our initiative and our community.

— Oliver Sacks, Abyssinian Baptist Church, New York, 31-MAY-2008.

W hat we have been studying ... is that when you pray, there’s actually a physiological change in the body. Music is very much a part of this. There are certain notes that generate in the human body a kind of peacefulness.”

— Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts III, pastor, Abyssinian Baptist Church, New York, 31-MAY-2008.

- DSM. Assistive Technologies 1: Wheelchair Transfers to Piano with Slide Board. CMT blog, 27-MAY-2008

- DSM. Assistive Technologies 2: Disability Arts and Special User Interfaces. CMT blog, 28-MAY-2008.

- World Science Festival website

- Oliver Sacks website

- Abyssinian Baptist Church. (“Believe. Build. Empower.”)

- AP. Neurologist, choir explore music’s healing power. New York Times, 31-MAY-2008.

- American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) website

- British Society for Music Therapy (BSMT) website

- Canadian Association for Music Therapy (CAMT) website

- Marilyn Maye website

- Abyssinian Baptist Choir. Shakin’ the Rafters. (Sony, 1991.)

- Chen J, Penhune V, Zatorre R. Moving on time: brain network for auditory-motor synchronization is modulated by rhythm complexity and musical training. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008; 20:226-39.

- Deutsch D, ed. Psychology of Music. 2e. Academic, 1998.

- Eldar E, Ganor O, Admon R, Bleich A, Hendler T. Feeling the real world: limbic response to music depends on related content. Cereb Cortex 2007; 17:2828-40.

- Grahn J, Brett M. Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. J Cogn Neurosci 2007; 19:893-906.

- Huron D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. MIT, 2008.

- Levitin D. This Is Your Brain on Music. Plume, 2007.

- Mithen S. The Singing Neanderthals. Harvard Univ, 2007.

- Mithen S. Singing in the brain: Music can change the way you think. New Scientist 23-FEB-2008, 2644:38-41.

- Nan Y, Knösche T, Zysset S, Friederici A. Cross-cultural music phrase processing: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2008; 29:312-28.

- Sacks O. Musicophilia. Knopf, 2007.

- Scherer M. Living in the State of Stuck: How Assistive Technology Impacts the Lives of People With Disabilities. Brookline, 2005.

- Snyder B. Music and Memory. MIT, 2001.

- Steinbeis N, Koelsch S. Comparing the processing of music and language meaning using EEG and FMRI provides evidence for similar and distinct neural representations. PLoS ONE. 2008; 3:e2226.

- Storr A. Music and the Mind. Ballantine, 1993.

- Toole J, Flowers D, Burdette J, Absher J. A pianist's recovery from stroke. Arch Neurol 2007; 64:1184-8.

- Watanabe T, Yagishita S, Kikyo H. Memory of music: roles of right hippocampus and left inferior frontal gyrus. Neuroimage 2008; 39:483-91.

No comments:

Post a Comment