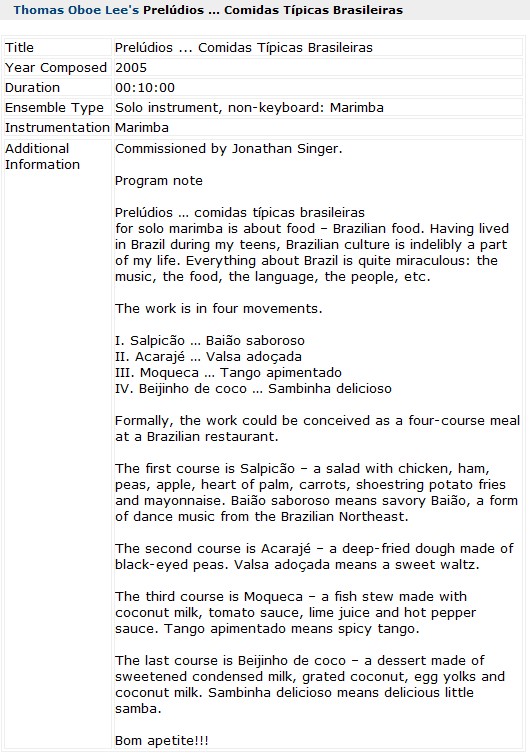

L ong before his death in 1954, at 80, Charles Ives seemed less like the father of American music than an eccentric uncle whose antic behavior and uncensored opinions at birthdays and funerals conscript his relatives into manufacturing an endless series of apologies and disclaimers... During the past decade, the picture of Ives has metamorphosed from eccentric uncle into cagey impresario and entrepreneur, a process explained by Gayle Sherwood Magee in her aptly titled ‘Charles Ives Reconsidered’... Magee’s book is a model of contemporary musicology—sympathetically sober in its judgments and interdisciplinary in its methods… Ives may have experienced every sound he perceived and every emotion attendant upon those sounds … as music. If we imagine this differently-eared, alternatively-wired Ives, a lot of what critics have found problematic about his music and career falls away. He probably possessed an acute and unaccountable impulse to use sounds expressively. As he matured, he had to balance the need to acquire skills through musical education against the preservation of this impulse.”

— David Schiff, review of Gayle Sherwood Magee’s Ives biography, ‘Charles Ives Reconsidered’, in The Nation 05-JAN-2009.

W hy do I work in this way and get all upset over what just upsets other people? No one else seems to hear [the music] in the same way [that I do]. Are my ears on ‘wrong’?”T he current issue of The Nation has a wonderful review by David Schiff, of the Charles Ives biography/musicological analysis by Gayle Sherwood Magee. Magee’s book is a delight. Schiff’s review is a delight as well.

— Charles Ives, response to violinists’ criticism of his Violin Sonata No. 1.

A t its best, good criticism genuinely returns the [Foucault-ian/Adorno-ian] ‘gaze’ of the subject whose work is reviewed. Not content to merely be constructive in explaining or characterizing what the work is/was, the best criticism is deeply original in its own right. It is no way ‘derivative’ or predictable or fashionable, nor does it parasitize the reviewed work by way of using the review as an occasion to massage the egos of others.

F ashion is fraud.”

— CrimethInc, Recipes for Disaster.

D avid Schiff’s essay is a wonderful example of excellence in criticism. He commends Gayle Sherwood Magee for her musicological scholarship and explains in detail the merits of her new book and the rationale for his judgment. These are not so much features of a distinctive authorly ‘voice’ but of an engaging authority—the friendly and well-tuned mind behind the voice.

W hat has been lost [in journalism in recent years] is the authority of the critic - his/her strength of voice. In an age where every opinion is valid, there are no more great critics in the mould of Bernard Shaw, Tynan, and Toynbee.”

— Mark Ryan, former Director, Institute of Ideas, London.

W ell, only if you ignore the work of David Schiff, Arthur Danto, and quite a few others.”S chiff goes (in the last page of his essay) well beyond the idioms of ordinary ‘review’ or criticism to reflect on the problems of doing biography and biographical musicology, including the vagaries of elusive personalities—subjects who [deliberately, cagily] left fragmentary and conflictual evidence, as a means of manipulating their own legacies and public personae. He poses additional novel possibilities that might account for Ives’s unusual career(s) and compositional output—stimulated in part by David’s recollections of his own father’s idiosyncrasies. He suggests entirely new avenues for medico-musicological exploration. He does this casually, in a three-page review, with a conversational style that reads like a letter from a friend or a transcript of a conversation in your living room.

— DSM.

In other words, Schiff’s review starts out reading like an excellent-but-conventional piece of criticism but gradually takes on some of the qualities of a Borges short-story—with conjectures that may or may not be feasible to pursue but are nonetheless captivating in their intriguing ‘No rules! Question everything!’ possibilities.

[50-sec clip, Bekova Sisters, Ives, Piano Trio, ‘I. Moderato’, 1.2MB MP3]

Ives pallido ci dice di iniziare ‘ma deciso a non mollare’ ... Okay. We begin playing decisively but mezzopiano then, as instructed, and without ‘letting go’. Wow. What an amusing notation in the first bar!

Ives’s 4 violin sonatas (1908, 1910, 1913-?14, 1906-?16) and 3 piano sonatas (1905, 1909, ‘Concord’ 1915) are well-known. There are good recordings of them; the pieces are relatively often performed—more often in conservatory recitals maybe than other programs or concert series, but still... The San Francisco-based Ives Quartet and Blair String Quartet do regularly perform Ives’s string quartets, as do others. The Miró Quartet will perform Ives’s Quartet No.1 on Friday 23-JAN at Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie in NYC...

T he Second Quartet is Ives in his early maturity, written between 1911 and 1913. The perplexing and sudden conjunctions, conflations, revelations, quotations and miasmic cuts are all firmly evident. But the somewhat tersely romanticised opening doesn’t quite prepare one for the fulminous writing to come: unceasingly powerful chromaticism. Here the quotations abound in tense, often hallucinatory rapidity... The [Blairs’] playing is involved and involving and conveys Ives’s journey from late Romanticism to modernism with conviction.”B ut Ives’s piano trio does not receive so much attention as it deserves.

— Jonathan Woolf, Musicweb International, FEB-2007.

A nd if your taste runs to the exotic or experimental, then there are other pieces of Ives’s chamber music that you may like to be aware of. Ives’s throw-down Fugues in B-flat and D; his bombastic Fugue in phrygian, hypolydian and dorian modes; his contemplative Largo for violin, clarinet and piano, for example.

O r his ‘Largo for piano quintet’, subtitled ‘Law of Diminishing Returns’? Quirky finance inspiration for an insurance-man-cum-composer! What the heck does that sound like, I wonder? Go to the Yale University library and check out a copy and find out! Or go to PeerMusic Classical who publish these unusual Largos Risolutos Nos. 1 & 2.

I ves in his last works finally regained his undiluted, uncompromised, uncontentious, and un-ironic compositional voice—the voice of innocence that he had left behind so long ago.”S chiff exposes impolite tastes, judgments and ideas for what they are. He lets the reader infer how unjust or ill-founded our received prejudices may be. In Schiff’s elegant 3-page essay, the indeterminate nature of Truth is laid a little barer than it has ever been, barer even than Magee has done. Without doubt, bare, original Truth is more beautiful than pretty verisimilitude. It is especially beautiful and surprising to find such beauty in a short review/criticism article in a publication for a general audience. Bravo!

— Gayle Sherwood Magee, Charles Ives Reconsidered, p. 162.

M agee’s efforts to debunk the medicalization/psychiatrification of Ives’s emotions are praised and synopsized in Schiff’s essay. But [‘It takes one to know one’] composer Schiff goes still further in normalizing Ives’s experimentality within the diversity of mainstream-composer personalities. To Schiff, every last one of us has his/her own unique ears and inspirations and obsessions, each her/his own skills and gifts and blind-spots. Not one of us is exactly like Ives, Schiff says, but neither was Ives any more aberrant or less aberrant in the spectrum of humanity than any of the rest of us is, lest auld acquaintance be rudely forgot.

H appy New Year! Peace!

D on’t pay too much attention to the sounds, for if you do you may miss the music.”

— George Ives, remarking to son Charles about the proper way to conduct hymns at a revival meeting.

- Schiff D. Ives’s ears. The Nation 2009; 288:30-3.

- David Schiff at Reed College

- David Schiff website

- Magee G. Charles Ives Reconsidered. Univ Illinois, 2008.

- Gayle Sherwood Magee at Univ Illinois Urbana-Champaign

- Journal of Music & Meaning website

- Music & Politics journal at UCSB

- Doctoral Dissertations in Musicology Online (DDMO) at Indiana Univ

- American Musicological Society website

- Empirical Musicology Review

- Blair String Quartet webpage at Vanderbilt

- Blair String Quartet at Vanderbilt Univ

- Blair String Quartet. Charles Ives: String Quartets. (Naxos, 2004.)

- Bekova Trio. Ives and Clarke Piano Trios. (Chandos, 2000.)

- Bekova Trio website

- Critics’ role in creating the artifacts of ‘history-as-exchange-economy’

- Ives Catalogue at Yale Univ

- The Charles Ives Society

- Adorno T. The Jargon of Authenticity. Routledge, 2006.

- Danto A. Unnatural Wonders: Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life. Columbia Univ, 2007.

- Roth M. Difference/Indifference: Musings on Postmodernism, Duchamp, and Cage. Routledge, 1998.

- Schiff D. The Music of Elliott Carter. Faber & Faber, 1998.

- Sinclair J. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Music of Charles Ives. Yale Univ, 1999.

- Smallman B. Piano Quartet and Quintet. Oxford Univ, 1996.

- Tuttleton J. A Fine Silver Thread: Essays on American Writing and Criticism. Dee, 1998.