Music is an art that exists in time. Music acquires its meaning through the interaction of all its parts. The unprepared listener is seldom aware of these interactions and may even be unable to identify the protagonists of the musical drama. He listens to music as a succession of individual moments, of greater or lesser beauty, never discovering the larger structures that give these moments meaning.”

— Halsey Stevens

CMT: One of my favorite memories of 2006 was a simple one—a ‘minimalist’ one, really. A peaceful one—related to my New Year’s wish for peace in the coming year. I’m remembering hearing some music by Arvo Pärt, during one of my trips to New York last spring when I was doing a project for an investment banking firm. As you know, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt dispensed with ‘new’ writing many years ago, and began instead to create ‘medieval’ pieces. Beyond the scope of his original intentions, he became fascinated with bells—carillons, campaniles, all sorts of bells. Exploring the harmonic qualities of each bell, and the idiosyncrasies of individual instruments, Pärt invented a new genre of atmospheric, spiritually satisfying, minimalist chamber music. Some people consider Pärt to be something of a music therapist. Others project onto him somewhat the role of prophet or mystic.

DSM: Pärt’s minimalism encompasses a broad range of moods and ‘affects.’ … Reminds me of Naomi Cumming—her ontology of minimalism, which includes ostinato techniques.

CMT: Pärt’s seminal work, ‘Fratres,’ was the focal point of that May concert by the Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players on Monday afternoon, 15-MAY-2006, at the Good Shepherd Presbyterian Church in New York (152 West 66th Street, west of Broadway). Vadim Gluzman, a violinist who was born in the Ukraine, offered his comments on what Arvo Pärt’s music meant to him and others in the context of Soviet oppression of composers and artists. In ‘Fratres,’ the soloist intones one note from each end of his/her instrument’s range, while the rest of the orchestra adds overtones. The result is a quivering, shimmering meditation. This effect can only be fully realized in the intimacy of a church or other early-music venue.

DSM: How does Pärt’s evocation of brotherhood— ‘frères,’ ‘fratres’—work? In theories of musical subjectivity, musical syntax usually gets primary attention. And most of the time, syntax is conceived as linear, sequential structure—something that’s parsed serially, although there may be ‘look-back’ and ‘look-ahead’ and other non-serial processing that our minds perform, just as our minds do for other linguistic forms. It seems to me that linear approach is overly simplistic—it does violence to the richness of the music, and it underestimates the complexity of our cognitive processes. It’s terrible—this forcing the round peg of the music into the square hole of an expedient sequential analysis.

CMT: The experience of Pärt’s ‘Fratres’ led me to think about what kinds of subjectivities are possible when musical syntax is undermined by ostinato motivic repetition. How is it possible for Pärt to evoke such a wide range of affects when his motives are so minimal!? And, yes, I did think about Naomi Cumming, whose book is about how music constructs the “musical subject”—the ‘who’ that listeners ‘become’ while they are engaged with a piece of music. Cumming says that construction of the subject involves the interaction of three elements: timbre, gesture, and syntax. Together they convey causality and intentionality—these elements create ‘implicative expectancies’ in the listener—through voice-leading, harmonic progressions, phrase-structure ‘grammars,’ and other devices. But what happens to the musical subject when syntax is undermined by a prolonged ostinato repetition of a single motivic gesture?

DSM: One explanation for wide-ranging expressive ‘affect’ is that not all ostinati are created equal, and none of them is really ‘static’. The effect of their continuation is longitudinally additive or cumulative—a Markov building upon the nearest-neighbor or immediate predecessor. Or maybe more like a soliton wave in physics. Richard Middleton offers a useful way to distinguish among different kinds of ostinati and their effects. Discursive repetition is repetition of longer syntactical units—whole phrases or strophes. I think Middleton and the hypermeter theorists and geophysicist/seismologists would have a lot to talk about!

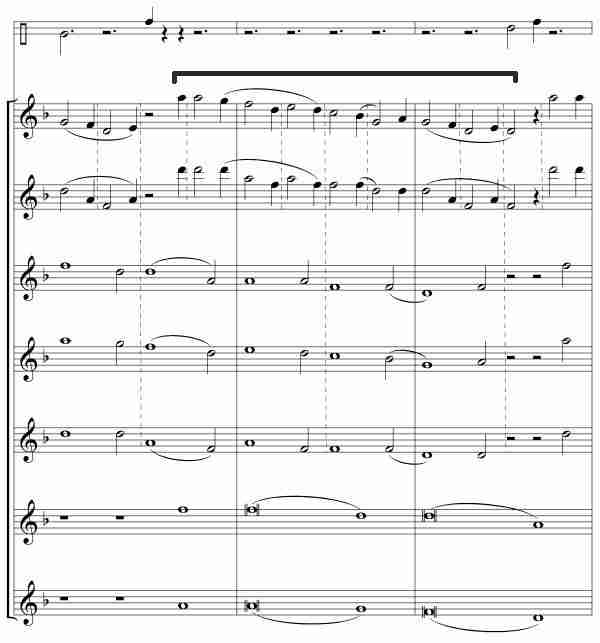

CMT: Middleton argues that a small-scale ostinato can passively achieve a degree of ‘psychic resonance’ for listeners, while larger-scale, discursive ostinato demands more of an active and ongoing emotional participation from listeners. Consider this example, from Arvo Pärt’s Arbos:

The ostinato phrase there is expansive. In fact, the phrase marked above the staves in square brackets is a longitudinally additive construct that originates many bars before the beginning of this excerpt. The repeated phrases are embedded within a canonical structure: units at the surface are generated from a slow-moving continuo background. Pärt creates other layers of the background texture to represent family ancestors to the generations in the foreground. Pärt’s structure evokes a whole cast of musical characters: the quicker foreground figures suggest present, active, live subjects, while background figures represent ancestors.

DSM: Because ostinati can be constructed and combined in many ways, a variety of different kinds of narratives can be expressed. Several features make Pärt’s Arbos and Fratres and other works mantra-like: the harmonic consonance and the limited timbre of a single diatonic mode are what evoke in me a serene and meditative state—what you were describing in your experience of the recital at Good Shepherd Presbyterian. But the carnatic repetition is part of a hypermeter build-up of small-scale ostinato elements into much larger-scale discursive units—this is what creates this mantra-type effect. And the relationships between the various orchestral and bell layers express a complex hierarchical organization that alludes to a community of mutually interdependent subjects, a world of people at peace.

CMT: But it’s not just about people and human-centric narratives. For example, some ostinato figures evoke indifferent, mechanistic, natural, seismic, non-human processes. This situation arises in works where the means of generating the repetitive motive is actually mechanical: think of Ligeti’s ‘Poeme Symphonique for 100 Metronomes’. What distinguishes the different types of ostinato is that each evokes a different musical subject—the conceit of repetition expresses different meanings. Ostinato repetition can serve many different expressive purposes. To understand something of the affective range exhibited by repetitive music, we have to look at the interplay of these repetition types, not just one of them in isolation. You have to look at the depth and granularity of hierarchical structures involving ostinati and figure out the associations between different types of hierarchies and specific moods, ‘affects,’ and subjects.

- Bartusiak M. Einstein's Unfinished Symphony: Listening to the Sounds of Space-Time. Berkley, 2003.

- Colpitt F. Minimal Art: The Critical Perspective. Univ Washington, 1993.

- Cumming N. The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification. Indiana Univ, 2001.

- Fink R. Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice. Univ California, 2005.

- Hillier P. Arvo Part. Oxford Univ, 1997.

- Jankelevitch V. Music and the Ineffable. Princeton Univ, 2003.

- Khan H. Mysticism of Sound and Music. Shambhala, 1996. (non-western chanting)

- London J. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford, 2004.

- Middleton R. Studying Popular Music. Open Univ, 1990. p. 247.

- Nattiez J. Music and Discourse. Princeton Univ, 1990.

- Potter K. Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Cambridge, 2002.

- Reich S. Writings on Music, 1965-2000. Oxford Univ, 2002.

- Rothstein W. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. Schirmer, 1990.

- Schwarz K. Minimalists. Phaidon, 1996 and 2007.

- Strickland E. Minimalism: Origins. Indiana Univ, 1999.

- Struble J. The History of American Classical Music: Macdowell through Minimalism. FoF, 1995.

- Yeston M. Stratification of Musical Rhythm. Yale Univ, 1976.

- Ligeti: Mechanical Music. (Sony, 1997.)

- Arvo Pärt: A Portrait (Naxos, 2005.)

- Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir. Arvo Pärt: Da pacem. (Harmonia Mundi, 2006.)

- Theatre of Voices. Arvo Pärt: De Profundis. (Harmonia Mundi, 1997.)

- Arvo Pärt website

- Jupiter Symphony Chamber Ensemble

- Arvo Pärt Wikipedia entry

- Arvo Pärt and the New Simplicity, radio interview 11-OCT-1998.

No comments:

Post a Comment