T he oxymoron ‘aural image’ highlights the special nature of musical ‘exemplarity’ and notational representation. Notated music examples are doubly distant from the aural phenomena that they represent: the notation stands for sound, but, excised and framed as example, points back to a presumed whole that it represents (synechdoche) and also forward from the new discourse of which it becomes a part... In moving from an analogical mode to an iconic one, the example itself becomes exemplar—inducing an imitative realization on the part of the audience.”C oncerts like the one that Tallis Scholars presented in Kansas City last night reconstitute iconic ‘things’ in their own likeness, by encompassing them as examples.

— Cristle Collins Judd, Reading Renaissance Music Theory, p. 5.

A s Cristle Collins Judd (Dean for Academic Affairs & Prof of Music Theory at Bowdoin) has written, examples are inherently ‘dependent texts’: they occur in the context of other/larger texts or discourses, which provide the framework by which we understand them and systematize them and recognize them and remember them.

T he holiday season and concerts that are performed during the holiday season are meta-exemplary? They abound in the recognizable. They leverage both tradition and memory to work their magic. As ‘exemplary’, they bring what’s ‘outside’ into the ‘inside’—inside the texts/discourses that they enlarge and annotate and illuminate as we listen and participate in the spell that’s being cast...

T here are, of course, discontinuities and rhetorical processes that aren’t discursive. The music; the program notes for the Tallis performance; the snippets of rendered music notation that we are able to review, etc.—are extreme in their ability to simultaneously provide streams of visual imagery and sonic stimuli along with the unfolding ‘text’.

W e delight in Josquin’s 6 usual Marian tropes—the delight made juicier by our knowledge that the Missa de beata virgine was later piously excised in the 22nd session of the Council of Trent, in 1562-1563.

I s my reveling at papal pique and Counter-Reformation vanity so wrong?

O h, the final cadences, enriched with thirds that Josquin did not put there. The mensuration of transitions resolved to clean, clear ‘sesquialtera’ completions that were not Josquin’s. The final notes’ durations lengthened or more notes added to tidy it up. Bare spots filled-in. ‘Tis a thing now of even greater beauty than it were in Josquin’s day...

I need to go to library and check out a copy of Sherr’s wonderful book (link below).

T his Tallis Josquin has got to be the most beautiful version of the Kyrie and Sanctus I have ever heard! Tallis’s Missa de beata virgine is a scholarly version, not a vehement or sentimental or valedictory one. I find the Tallis Scholars’ approach brings a new freshness to the piece that I can’t help but prefer. In particular, the soprano, countertenor, and alto parts have a lovely tone and some soul-stirring melodies above the lower voices. The friendly acoustics of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception lends extra warmth to the endeavor.

P hillips’s conducting—and the responsiveness of the ensemble to his direction—are the causes of the vibrancy and freshness. And just watch! The ‘vibrancy’ is explicit, demanded by Phillips’s hand gestures on many downbeats and on fermatas. So besides the notation and the ‘aural image’, we have the visual image of the conductor and the choir...

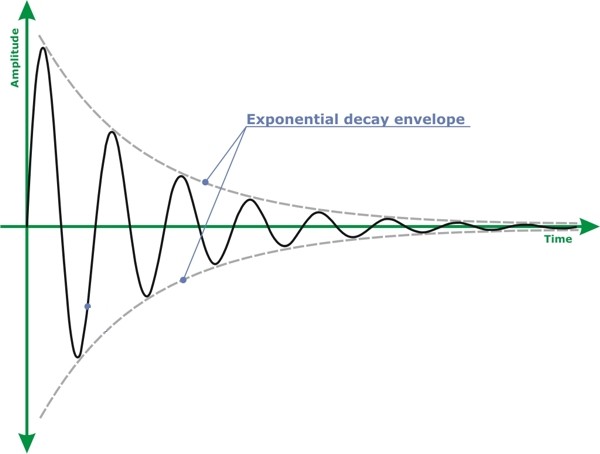

P hillips’s hands extend outward from his waist, oscillating in a diminuendo—the amplitude of the hand vibrations decays from 2 centimeters, peak-to-peak, to zero centimeters over a period of a second or so. The waveshape of the gestural decay is approximately exponential each time, with a time constant 1/λ equal to about 200 milliseconds. He does this throughout the performance; it is clearly a core idiom of Phillips’s personal conducting language.

A(t) = A0exp(-λt)

T his is not a ‘bouncy’ gesture. Instead, it suggests exquisite ‘tautness’, controlled impulsion—an equine sort of ‘puissance’ being brought gracefully to rest. It reminds me specifically of a manner of applying ‘leg aids’ to the flanks of your horse when you are bringing your horse to an elegant halt in the dressage ring.

W hat I mean to say is, this choral ensemble ‘animal’ loves its work, and it aims to utterly please. And the choral ‘rider’ [Phillips] loves the suppleness and compliance he finds in the animal, and his subsequent hand ‘aids’ generously adapt to the eager suppleness that’s displayed by the animal.

W hat we see and hear, then, is this sublime unity of the joy of conducting and the joy of singing, the joys of riding and of being ridden. Spirituality through innocent, virtuosic carnality. Maybe that’s what the Council of Trent was worried about.

A usterity, logic, and Josquin’s complete command of compositional form and contrapuntal symmetry permeate [Missa de beata virgine], suggesting a purity of conception meant to please God in its perfection—not excite the passions of men and women.”

— Peter Phillips, Tallis Scholars Programme Notes, 10-DEC-2009.

- Tallis Scholars website

- Peter Phillips website

- Choral conducting books at Singers.com

- Tallis Scholars Christmas. (Gimell, 2003.)

- Tallis Scholars. Josquin: Missa sine nomine; Missa ad fugam. (Gimell, 2008.)

- Gangwere B. Music History During the Renaissance Period, 1520-1550: A Documented Chronology. Praeger, 2004.

- Gelley A. Unruly Example: On the Rhetoric of Exemplarity. Stanford Univ, 1995.

- Harr J. The Science and Art of Renaissance Music. Princeton Univ, 1998.

- Judd C. Reading Renaissance Music Theory: Hearing with the Eyes. Cambridge Univ, 2006.

- Cristle Collins Judd page at Bowdoin

- Monson C. The Council of Trent revisited. J Am Musicol Soc 2002;55:1-37.

- Craig Monson page at Wash U.

- Sherr R, ed. The Josquin Companion. Oxford Univ, 2001.

- Sparks E. The Music of Noel Bauldeweyn. AMS, 1972. Pp. 40-1.

- Missa de Beata Virgine page at Wikipedia

- Bicinium scores